Blog + News

Moodys Tax Explains Canada Emergency Wage Subsidy (CEWS) v. 2.0

Want to attend a July 27 live webinar and Q&A on CEWS 2.0 by the authors? Register today.

Want a short one-on-one consultation with a Moodys professional? Sign up today.

The ongoing wage subsidy saga is a perfect case study of the dilemma faced by drafters of tax legislation: Should tax legislation be drafted broadly so as to impact everyone equally despite the fact that it may not be fair, or should tax legislation be drafted in a bespoke manner that is carefully targeted to achieve a perceived fair and progressive outcome but that inevitably comes with complexity? With the COVID-19 wage subsidy regime, we have witnessed the full spectrum.

The first wage subsidy introduced in response to Covid was the Temporary Wage Subsidy (TWS) announced on March 18, 2020 – see our blog on this. Although the subsidy was not substantial (10% of wages paid, up to $1,375 per employee to a maximum of $25,000 total per employer), it was spectacularly simple. Many employers in Canada qualified for the TWS. It was not progressive because businesses that did not suffer under the crisis got the same TWS amount as the businesses that were completely closed down. Everyone was treated equally, but it was not necessarily fair.

Then, with great interest, came the Canada Emergency Wage Subsidy (CEWS) on April 1, 2020. The CEWS can be a very substantial amount to an employer (up to $847 per week, no maximum limit, with a refund of the employer’s portion CCP and EI for a furloughed employee). Unlike the TWS, CEWS 1.0 is targeted: only employers who suffered a 30% decline in revenue can benefit and it came with a heap of rules to siphon out those who do not truly qualify (which is understandable given the potential for abuse of the program). As a result, the CEWS legislation was quite complex. Yet, at the same time, the 30% all-or-nothing cut off was a clear attempt to balance this targeted approach with simplicity. The legislation could have included a phase-out mechanism based on the exact revenue decline, but it chose not to do so for ease of administration and so that a layperson can somewhat grasp the overall concept of CEWS.

It is now more than three months after the first introduction of CEWS. Many businesses have started re-opening (while many businesses, very sadly, did not survive). The Government’s priority has shifted from “Holy Guacamole, Just Push Cash Out the Door Already!” to providing the right economic incentives to businesses and workers for the recovery. The result is a completely overhauled CEWS subsidy released by the Government on July 17, 2020 (almost exactly 3 years to the day of the release of the complex and now famous July 18, 2017 private corporation tax proposals). Some have called this “CEWS 2.0”, and we’ll use this term too.

CEWS 2.0 no longer uses an “all-or-nothing” approach. Instead it uses multiple sliding scales that adjust the amount of CEWS support based on the exact revenue decline. In circumstances of severe business decline, it may even result in CEWS being higher than under the current mechanics. As you will see, CEWS 2.0 attempts to employ a very bespoke mechanic that should deliver the perceived ‘right’ amount of CEWS in various different circumstances – and we certainly appreciate the Government and particularly the legislation drafter at the Department of Finance for the tremendous thought that went into this new piece of legislation. Unfortunately, this bespoke-ness brings immense complexity that many will struggle to understand. Even the Government Backgrounder, which is supposed to be a non-technical briefing document, needed 22 pages and six elaborate tables to illustrate the formulas behind new CEWS mechanics.

Critics have described CEWS 2.0 as “massively complicated” and “a cobweb of complexity”. These are accurate descriptions of the new rules, but complexity is sometimes a necessity when the policy goal is to accurately assess needs and to selectively scale subsidies based on those needs. Of course, if the policy were to implement some type of universal basic wage subsidies where all employers qualify for the same amount, then the rules could have been simple – all they need is to reuse the TWS legislation and slap a high subsidy rate on it. This, however, was not the route chosen by the government and since we are not economists, we will decline to comment on which is a better policy choice.

In a short span of three and a half months, we have three versions of wage subsidy rules that ran this full spectrum of broad vs targeted. For tax geeks like us, it is amazing to see classroom theories on legislative principles put into practice like this. But, enough with our babbling, let’s see what’s under the hood of CEWS 2.0.

A FlowChart is Worth A Thousand Words

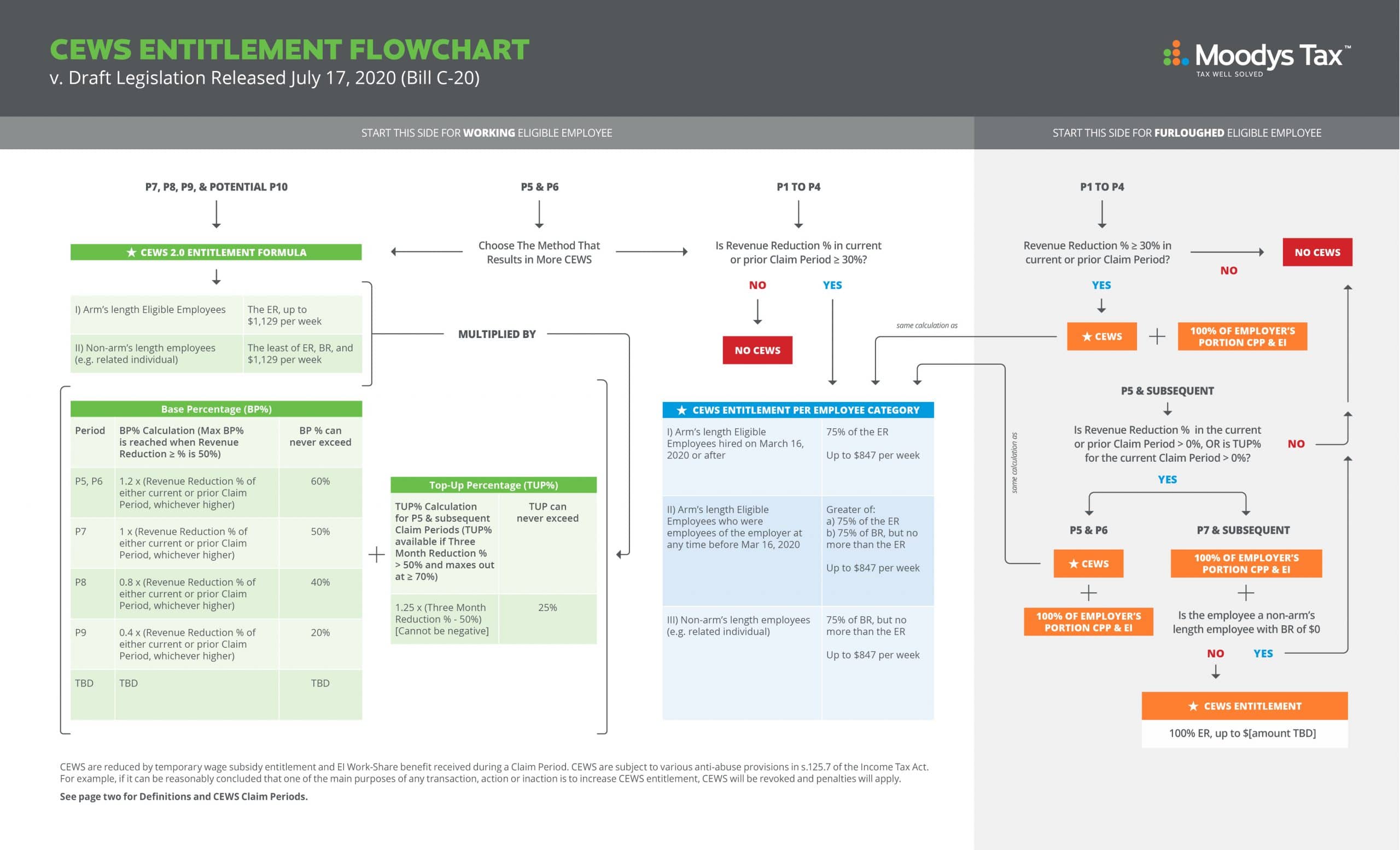

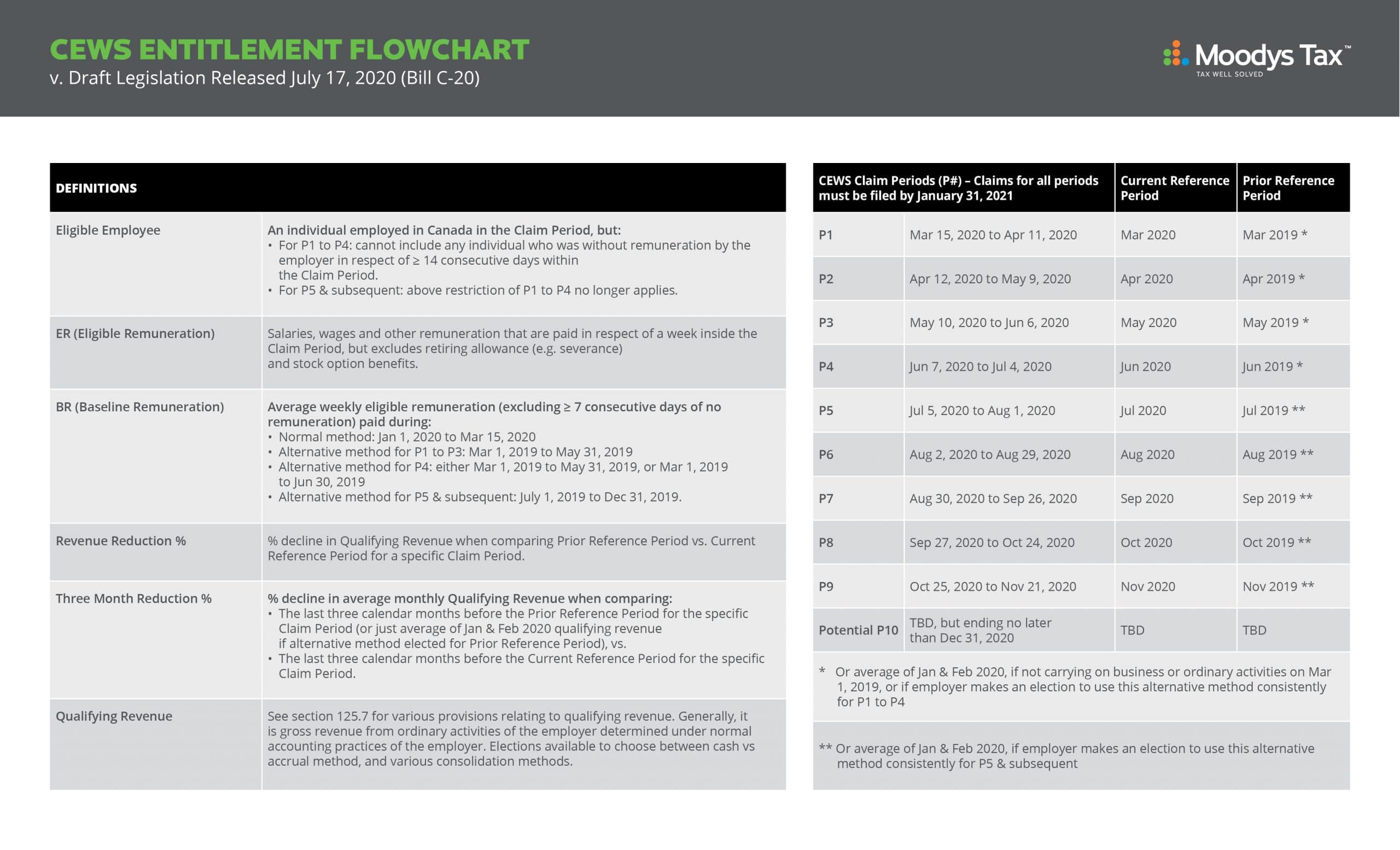

We said CEWS 2.0 is complex and we weren’t kidding. The combined original and draft legislation on CEWS is a 26-page word salad with many circular references. Rather than attempting to explain the entire CEWS mechanics with words, we decided that the CEWS 2.0 mechanics is best explained with a FlowChart. The FlowChart is divided into active versus “furloughed” eligible employees. Furloughed employees are those who are paid wages by the employer but are on leave (i.e. not performing any work). The government’s goal was to provide further incentives for employers who are suffering under Covid to hire back employees and have them furloughed, rather than the employees receiving CERB benefits.

If you were familiar with the existing CEWS program, you will notice the following changes to the CEWS program that are illustrated in the FlowChart above:

- The CEWS program is being expanded to November 21, 2020 (a total of nine Claim Periods), and potentially to the end of December 31, 2020 (by regulation).

- The CEWS calculation for Periods 1 to 4 remains the same – which makes sense, since those periods have already passed, and funds have been paid out.

- For Period 5 and Period 6, an employer will calculate CEWS based on the old method (CEWS 1.0) and the new CEWS 2.0 methodology and will get the higher of the two figures.

- For Periods 7 and subsequent periods, employers must use the CEWS 2.0 methodology.

- The deadline for filing CEWS submissions for all Claim Periods is pushed out to January 31, 2021 (from September 30, 2020 previously).

- The CEWS 2.0 methodology calculates CEWS entitlement based on the revenue decline of the current month (the Revenue Reduction % in the FlowChart) and the average prior three months (the Three Month Reduction % in the FlowChart). The Revenue Reduction % controls the “base percentage” (BP%), which calculates a scaled base CEWS amount for any employers who suffered more than 0% revenue decline. BP% reaches its maximum when revenue declined by 50% or more. The Three Month Reduction % controls the “top-up percentage” (TUP%). TUP% adds a top-up CEWS amount for businesses that suffered a Three Month Reduction % of over 50%, and it scales up until the revenue decline reaches 70%.

- The employer can calculate the BP% based on the greater Revenue Reduction % of the current and prior Claim Period.

- Different alternative methods for determination of “baseline remuneration” may be elected for different Claim Periods.

- Under the existing CEWS regime, employees cannot be Eligible Employees for the CEWS if they were without remuneration in respect of 14 or more consecutive days in a Claim Period. For Period 5 and going forward, this restriction no longer applies. Employers no longer have to worry about not qualifying for CEWS when they hire new employees (or hire back previously laid off employees) during a Claim Period.

- For Period 5 and going forward, CEWS can be claimed for furloughed employees as long as it has a Revenue Reduction % or TUP% of over 0%. At first glance the 0% threshold appears overly generous, but the Government likely anticipated that businesses whose revenue did not decline significantly will not be inclined to furlough their employee since the CEWS does not cover the entire paycheque.

- If an employer has previously elected to use the average of January/February in determining their prior reference period (the alternative approach), they may now choose to use the previous year comparable month (the general approach) for Period 5 onwards. Vice versa, an entity that used the general approach for Period 1-4 may now elect to use the alternative approach rather than the general approach for Period 5 onwards.

- If an entity elected to use the cash accounting method previously, this does not appear to be able to be changed. The election still applies for all qualifying periods.

The FlowChart purposely does not dive into the nuances of the calculation of “qualifying revenue”. Other than certain changes described below, the determination of qualifying revenue remains the same as the existing CEWS regime. You can read our previous CEWS blog for discussions on qualifying revenue.

Other Changes in CEWS 2.0

Qualifying Revenue Definition

As it is currently legislated, and as we have previously discussed, subsection 125.7(1) provides the definition for “qualifying revenue” for purposes of CEWS. The basic definition did not change, and the only addition was a new paragraph (b) which allows “prescribed organizations” that are registered charities or non-profit organizations to choose whether to include government source revenue.

Cash Accounting

Under the current legislation, an eligible entity may elect to use the cash accounting method rather than the ordinary accrual method. However, farmers, fishers, and self-employed commission agents who may ordinarily use the cash accounting method had no ability to use the accrual method. Bill C-20 provides relief to these persons who may now elect to use the accrual method (in accordance with generally accepted accounting principles) in the determination of its qualifying revenues for CEWS.

Amalgamations- Eligibility for Predecessor Corporations

In our previous blog, we discussed the technical issues in the legislation regarding CEWS eligibility if an amalgamation occurred. The draft legislation contained in Bill C-20 solves the continuity issue if a corporation underwent an amalgamation. Paragraph 87(2)(g.5), as it is proposed, provides that for the purposes of section 125.7, the new corporation is deemed to be the same corporation as, and a continuation of, each predecessor corporation. The caveat to this continuity rule is that if one of the main purposes of the amalgamation is to cause the new corporation to qualify for CEWS, or to increase the amount of the CEWS benefit, paragraph 87(2)(g.5) will not apply to deem the new corporation to be the same corporation as the predecessor corporations. This new legislation will allow an amalgamated corporation to calculate benchmark revenue for the revenue decline test. This proposed change is retroactive to April 11, 2020, which means companies that may have not historically qualified due to an amalgamation should revisit their calculations to determine if they now qualify.

Asset acquisition reserve test continuity election

The proposed legislative amendments include new provisions for dealing with the acquisition of a business during a reference period. Under the current regime, if an eligible entity purchased all or part of a business in between its prior reference period and its current reference period, then that business may not meet the revenue drop test, despite its pre-COVID revenues dropping by 30% or more.

For example, a business with $100K per month of revenue for 2019, doubled its size by buying a similar business with $100K of monthly revenues at the end of February 2020. Subsequent to the acquisition, all parts of the business suffered a revenue decline of 40%, so that revenue per month became $120K. Under the current rules, that business would not qualify for the wage subsidy unless its revenues dropped by at least 65% (revenues would need to drop from $200K per month to $70K per month to qualify). The current rules do not contemplate situations in which a structural change of the business caused a large revenue increase in the past 12 months (or after February 2020 under the alternative prior reference period method). This was a significant flaw in the legislation, as the business did suffer a significant revenue reduction (more than 30%) relating to both its pre-acquisition assets and post-acquisition assets, but due to the increase in its size from the prior reference period, the business could not reach the 30% revenue decline threshold. This seemed to be against the spirit of the legislation and the wage subsidy in general.

Proposed subsections 125.7(4.1) and (4.2) attempt to correct the flaw in the legislation by accommodating asset acquisitions.

Subsection 125.7(4.1) contains the following eligibility requirements:

(a) the eligible entity acquired assets (referred to in this subsection and subsection (4.2) as the “acquired assets”) of a person or partnership (referred to in this subsection and subsection (4.2) as the “seller”) during the qualifying period or at any time before that period;

(b) immediately prior to the acquisition, the fair market value of the acquired assets constituted all or substantially all of the fair market value of the property of the seller used in the course of carrying on business; (We note that the use of all or substantially all is interpreted by the CRA as 90% or greater, but the Courts are generally more flexible)

(c) the acquired assets were used by the seller in the course of a business carried on in Canada by the seller;

(d) it is reasonable to conclude that none of the main purposes of the acquisition was to increase the amount of [the CEWS]; and

(e) the eligible entity elects in respect of the qualifying period and files the election in prescribed form and manner with the Minister or, if the seller is in existence during the qualifying period, the eligible entity and the seller jointly elect in respect of that period and so file with the Minister.

If the conditions in subsection 125.7(4.1) are met, then subsection 125.7(4.2) allows the eligible entity to include the qualifying revenue attributable to the acquired assets that was earned by the seller (defined in this subsection as the “Assigned Revenue”) in the eligible entity’s relevant prior reference period or current reference period for the relevant qualifying period.

The Assigned Revenue is subtracted from the “qualifying revenue” of the seller for the relevant reference period.

Additional modifications are also made to ensure that non-arm’s length revenue of the seller are not excluded from qualifying revenue of the eligible entity and the requirement that the eligible entity have a payroll number by March 15, 2020 is deemed met if the seller met that requirement.

These proposed changes only apply if the fair market value of the acquired assets constituted all or substantially all (CRA tends to consider substantially all as 90% or more) of the fair market value of the property of the seller used in the course of carrying on business. This requirement will exclude many asset acquisitions, purely based on the circumstances of the seller. The result appears unfair to buyers that may not qualify for the wage subsidy due to conditions outside their control.

For example, a buyer may qualify if the seller segregated its enterprise among several different corporations. However, a buyer may not qualify if the seller had different businesses in the same corporation or only sold a portion of its business.

The assignment of revenue and reduction of the seller’s revenue for the relevant qualifying periods suggest that Finance is concerned with two businesses claiming the wage subsidy for the same qualifying period. This concern could have been dealt with in other ways than limiting the eligibility for this election.

If the seller is still in existence during the relevant qualifying period, a joint election by the buyer and seller is required. This election may be outside the scope of any covenants made by the seller in the purchase and sale agreement. If so, buyers may find it difficult to get sellers to agree to the joint election. The seller should have qualified for the wage subsidy due to selling all or substantially all of its assets, and despite that sale, it may still have employees for which it has claimed the wage subsidy. More likely, there is just no incentive to cooperate with the buyer.

Buyers of assets may also not have detailed sales and accounting records to substantiate the assigned revenue. Those buyers will need sellers to provide that information and will need to rely on the seller for accuracy. We question how cooperative sellers will be in executing a joint election and if these modifications to the wage subsidy will be effective given the uncertainty for buyers.

Tax Disputes

As we previously blogged, there is, and will continue to be, significant audit activity regarding CEWS claims. There were questions on how this mechanically would work, as CEWS was a deemed overpayment of tax. Bill C-20 now proposes (by way of adding subsection 152(3.4)) that the Minister may “determine the amount deemed by subsection 125.7(2) to be an overpayment on account of a taxpayer’s liability under this Part that arose during a qualifying period, or determine that there is no such amount, and send a notice of determination to the taxpayer” (emphasize added). This change is retroactive to April 11, 2020. As a notice of determination, a taxpayer can now formally object to the notice of determination (within 90 days, or by way of a request, one year plus 90 days from the date of the notice) and further appeal to the Tax Court of Canada, as if the determination were an assessment.

Third Party Payroll Providers

Under the currently enacted legislation, in order to be a “qualifying entity” (and therefore qualify for CEWS), an entity must have a payroll remittance number with the CRA as of March 15, 2020. Many businesses use a centralized payroll service in order to handle all payroll matters for its employees. Even if these businesses had a 30% revenue decline, as they did not have their own payroll account number, they did not qualify for CEWS.

Bill C-20 now contains draft legislation that would allow these entities to qualify. This is accomplished by amending the definition of “qualifying entity”, to either require the entity to have a payroll number itself, or, on March 15, 2020, the entity employed individuals in Canada, had its payroll administered by another person or partnership, and the payroll service provider had a payroll account number, and the payroll service provider used its business number to make the appropriate remittances for the employees of the entity.

This change should provide significant relief to many businesses, as a centralized payroll provider is quite common in many industries, particularly in the medical services field.

Concluding Comments – How Will CRA Keep Up??

By virtue of the CEWS 2.0, all employers who suffered (or will suffer) a revenue decline of more than 0% will qualify for some amount of CEWS. This means a substantial majority of all businesses in Canada may now apply for CEWS. If CRA was not overwhelmed before these changes, its processing and audit departments may not now be able to keep up with the number of applications. The CRA call centres’ phone lines will undoubtedly be ringing off the hook from businesses and advisors trying to understand the increased complexity of the program. Once CEWS audits start, which from what we heard, will likely be in 2021, CRA’s objections will be next in line to be overwhelmed. The Auditor General has already concluded that the CRA historically does not process objections in a timely manner, and does not provide correct answers to taxpayers on the phone. This will only compound these issues, with how complex the legislation is.

Canadian tax practitioners will be dealing with CEWS for years. (And then, maybe finally, we will agree on the correct way to pronounce “CEWS”).

In the meantime, a thorough review of the FlowChart should be done by all Canadian businesses. Happy reading!

Related Blogs

Have you ever wondered how much your US citizenship is costing you? Why renouncing could save you hundreds of thousands and open new doors for financial opportunities.

As US expats prepare for another expensive and stressful tax filing season, we’ve compiled a list of...

Looking to make 2024 your last filing year for US taxes? Here’s what you need to do.

In a recent survey, one in five US expats (20%) is considering or planning to renounce their...

Travelling to the US? If you’re a US expat who doesn’t renounce properly, your trip may never get off the ground.

Air travel can be stressful. Rising airfares and hotel costs, flight cancellations, pilot strikes, long security wait...