Blog + News

Bill C-14 – The 75% Canada Emergency Wage Subsidy (CEWS) – Detailed Overview and FAQs [Updated May 26, 2020]

We have been very pleased by the response to this blog from business owners and practitioners from across Canada. The appetite for this information is enormous and the questions numerous due to the complexity of the legislation. Many have been asking very good questions and providing excellent feedback. Some of the feedback has resulted in changes to the original version of this blog to improve clarity or correct errors. We thank people for the feedback and encourage it to continue. In particular, the following updates to the original version of the blog have been made:

- March 15, 2020 in respect of a pre-existing arm’s length employee could potentially increase the CEWS entitlement, and that the same cannot be done for non-arm’s length employees. Thanks Tim! In addition, Harvey Dykes from Vancouver pointed out a mathematical error in the original version of this example and it has now been corrected. Thanks Harvey!

- April 14, 2020 – Christy Holland, CA of Wormald Masse Keen Lopinski LLP pointed out an error we made in our Facebook Live and in the original version of our blog regarding the default (comparing 2020 month to corresponding 2019 month) and alternative (comparing 2020 month to the average of January / February 2020) method in regards to the revenue decline test. In no situation can a CEWS applicant flip-flop between the two methods. The blog has been updated to reflect this correction and we advise viewers of the embedded Facebook Live to not rely on our original comments made about this issue. Thanks Christy!

- April 15, 2020 – Tim Duholke, FCPA, FCA of Kabro Strategies Inc. provided commentaries that led us to include an expanded discussion of how to deal with pre-existing arm’s length employees and updated the Krusty Krab / Plankton example. The example now clarifies that remuneration increases after

- April 15, 2020 – Mark Klingbaum , M.Acc., CPA, CA, TEP of Klingbaum Barkin Professional Corporation helped us expand our FAQ on applying the revenue decline test to cross-border affiliated group situations, and how the revenue decline test may not work properly for many such situations. Thanks Mark!

- April 15, 2020 – We have updated our comments on CERB to reflect that those making $1,000 or less a month are still eligible for CERB.

- April 17, 2020 – Justin Abrams, CPA, CA of Kraft Berger LLP identified the ability to switch between consolidation and non-consolidation basis of determining qualifying revenue from one Claim Period to the next. We have added this discussion to our FAQ.

- April 26, 2020 – Updates based on CRA’s FAQ: April 27 application start date, ability for authorized representative to apply, CRA’s intention to publish registry of CEW applicants, retroactively hiring of employees, clarification about the onus on CERB eligibility being on the employee and not the employer, reduction of CEWS for the 10% wage subsidy even if payroll remittance has not been reduced, the CRA’s ability to withhold CEWS from seriously non-compliant taxpayers, and CEWS T4 reporting requirements.

- April 26, 2020 – Based on discussion with John Oakey, CPA, CA, TEP, CC of Baker Tilly, we updated the discussion of qualifying revenue to add that the “inflow of cash, receivables and other consideration” language parrots the ASPE definition of revenue. There is a corresponding change to the FAQ on work-in-progress.

- April 26, 2020 – Added a FAQ on CEWS computation when pay period does not align with Claim Periods.

- May 13, 2020 – the Government introduced an election to reduce the entitlement to the temporary wage subsidy from 10% to 0%. This impacts the computation of CEWS.

[/toggle-box]

On Saturday April 11, 2020, Canada’s Parliament met to debate and hurriedly pass legislation contained within Bill C-14 – COVID-19 Emergency Response Act, No. 2 (the “Bill”). Later that same day, both the House of Commons and the Senate passed the Bill which subsequently received Royal Assent. The Bill implements the 75% Canada Employment Wage Subsidy (“CEWS”) which the government first announced almost two weeks ago. The government webpage on CEWS was also been updated to reflect the Bill. While parliamentarians and certain media had access to the Bill for some time, Saturday was the first opportunity for the public to view its contents. Although many businesses will no doubt benefit from this new legislation, our core concern about the complexity of the program remains. The legislation is very complex and will, without a doubt, be beyond the comprehension of the average business owner. The CEWS application is expected to be available starting April 27, 2020, and in most cases, it is anticipated the cash will be available through direct deposit within 10 business days of the application.

The government published a frequently asked questions (FAQ) webpage on CEWS on April 24, 2020, a few days before the CEWS application goes live. Even though the content did not stray from basic scenarios and did not get into the many uncertainties in the application of the rules, it does provide a few useful numeric illustrations to help businesses understand the basic mechanics.

Our comments follow.

An Overview of the CEWS Legislation

Notable changes from April 8, 2020 announcement

For those following the development of the CEWS closely through the government announcements preceding the Bill, below are the notable differences between the CEWS program as last announced on April 8, 2020 and the actual legislation enacted:

- The CEWS program is enacted by introducing new section 125.7 of the Income Tax Act (the “Act”) with other various companion amendments throughout the Act;

- The Bill provides an approach to deal with payroll entities and other complex corporate structures / groups when applying the revenue decline test;

- We are delighted to see that once an employer is found to be eligible for a specific period, the employer would automatically qualify for the next period. This somewhat removes our fear that the CEWS program may dis-incentivize some businesses from trying to recapture their lost revenues over the next couple months. Also, in some circumstances, it provides certainty to business owners that they will qualify for an upcoming month without having to ‘predict’ future revenues;

- Wages paid to employees who are without remuneration by the employer for 14 or more consecutive days in the qualifying period will not qualify for CEWS. Previous announcements described the test as “more than 14 consecutive days” – we discussed how this was an error in our previous blog;

- A number of anti-abuse rules are embedded in the legislation. We will outline them below;

- The Bill gives the Minister power to extend the CEWS program to September 30, 2020 without having to recall Parliament. Currently, the Bill provides for the CEWS program to end June 6, 2020;

- The Bill gives the Minister the power to make public the name of any persons who applied for CEWS, presumably to punish those who the government think did not put the CEWS money to its intended use. This type of “name and shame” with a tax incentive program sets a dangerous precedent and, in our opinion, was not necessary. The government FAQ (#35) made it clear that the CRA will publish a list or registry of CEWS applicants.

Who may apply?

A “qualifying entity” – as defined in new subsection 125.7(1) of the Act – may apply for CEWS. Taxable corporations, individuals, registered charities, most non-profit organizations, and partnerships with these entities as members may all potentially be qualifying entities. To qualify, the entity must have a payroll remittance number with the Canada Revenue Agency (“CRA”) as of March 15, 2020, and the entity must meet the revenue decline test.

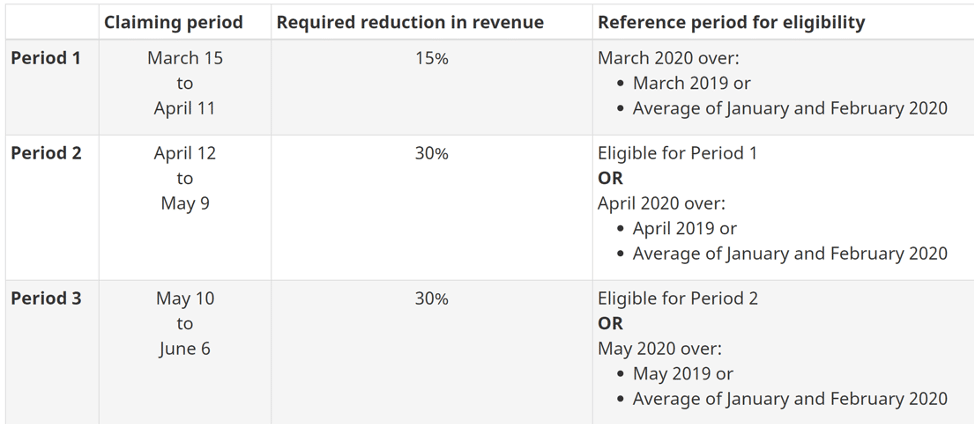

The below chart summarizes the revenue decline test for each of the three claim periods:

These Claim Periods are technically defined as “qualifying period” in subsection 125.7(1) of the Act, but we refer to them as Claim Periods 1, 2, and 3 throughout this blog to refer to these three distinct periods.

As described above, the revenue decline test looks at whether the “qualifying revenue” – as defined in new subsection 125.7(1) of the Act that will be discussed further below – for the reference period has declined at least 15% (for Period 1) or 30% (for Period 2 and 3). For Period 1, the revenue decline test is met if the qualifying revenue during March 1 to March 31, 2020 was 15% lower than the qualifying revenue during March 1 to March 31, 2019. The same logic applies for Periods 2 and 3 but the required decline becomes 30%. Alternatively, the month in 2020 may be compared to the average qualifying revenue in January and February 2020 in one of two situations:

- On March 1, 2019, the employer was not carrying on business or its ‘ordinary activities’;

- Or the employer makes an election to use the alternative method for consistently all of Claim Periods 1, 2 and 3.

This means that an employer who was not carrying on business or its ‘ordinary activities’ must use the alternative method of comparing each of March, April and May 2020 to the average qualifying revenue of January and February 2020. Whereas an employer who was carrying on business or its ‘ordinary activities’ as of March 1, 2019 may either use the default method (comparing the month in 2020 to the corresponding month in 2019) for all Claim Periods or elect to use the alternative method of comparing the 2020 month to average January/February 2020 for all Claim Periods. In no scenario can an employer flip-flop between the two methods.

The computation of the average January and February 2020 qualifying revenue is based on a formula which takes into account days on which the employer may not be carrying on business during those two months.

As mentioned earlier, meeting the revenue decline test for a Claim Period means that the revenue decline test for the immediately following Claim Period is also met because of the new deeming provisions set out in subsection 125.7(9) of the Act. For example, an employer that meets the 15% revenue decline test for Claim Period 1 will automatically be considered to meet the 30% revenue decline test for Claim Period 2 (note: it will still have to meet other requirements besides the revenue decline test for Claim Period 2). This rule does not extend further than the immediately following Claim Period, meaning that employer must actually meet the 30% revenue decline test for May 2020 in order to qualify for Claim Period 3.

The revenue decline test is based on “qualifying revenue” during the months being tested. What does this term mean? The legislation defines “qualifying revenue” as the

- “inflow of cash, receivables or other consideration arising in the course of the ordinary activities of the [employer] – generally from the sale of goods, the rendering of services and the use by others of resources of the [employer] – in Canada in the particular period”

- “It excludes, for greater certainty, extraordinary items”

- “It excludes amounts derived from persons or partnerships not dealing at arm’s length with the [employer]”

- “It excludes, for greater certainty, [any CEWS claimed and any entitlement to the 10% wage subsidy]”

All of the above is to be determined in accordance with the employer’s “normal accounting practices” (a new phrase introduced in subsection 125.7(4) of the Act), but an election can be made to determine revenue on the cash method instead for all Claim Periods. For some, the revenue determination may be very straight forward. But for some businesses, this elaborate definition raises many questions. What are “other consideration”, “course of the ordinary activities”, and “extraordinary items”? These are not terms defined in the Act. While accounting principles may provide guidance, accounting principles are designed to be flexible and open to interpretation. Such room for interpretation is dangerous here, given the harsh penalties of wrongly applying for CEWS. Even identifying the so-called “normal accounting practices” may be an uncertain exercise in many circumstances.

Also, we know from government announcements that qualifying revenue is not supposed to include amounts on account of capital (i.e. proceeds from sale of a capital property). You would think the legislation would provide for an explicit exclusion for something this common, but it does not. Under most accounting principles, the computation of revenue does exclude proceeds from the sale of capital properties. However, can we simply import the accounting definition of revenue for this purpose? If that was the intention, why didn’t the legislative definition of “qualifying revenue” tell applicants to make “revenue” their starting point? Instead, the definition of qualifying revenue tells applicants to include “inflow of cash, receivables or other consideration arising in the course of the ordinary activities…”. A sale of a capital property certainly brings an inflow of cash or receivables.

Is the sale of capital properties excluded because it is not “in the course of the ordinary activities”, or because it is an “extraordinary item”, or perhaps it should not be excluded after all? For example, one of our firm’s clients has been selling off rental properties on a regular basis before and during the crisis due to the Alberta economic slowdown. Should those proceeds be included in the computation of qualifying revenue since the inflow of cash from those disposition proceeds have lately become that person’s “course of ordinary activities”? Since “sale of goods” is explicitly included in qualifying revenue, should the sale proceeds of some capital property that can be considered “goods” be included? Wikipedia – the font of all wisdom – defines goods as “commercial goods are construed as any tangible product that is manufactured and then made available for supply to be used in an industry of commerce”. That’s pretty broad.

To be fair, the “inflow of cash, receivables or other consideration” is very similar in wording to the definition of revenue contained in section 3400 of the Canadian Accounting Standards for Private Enterprises (ASPE). Perhaps the answer simply is that if capital proceeds are typically excluded from ASPE revenue under the employer’s normal accounting practices, it should not be included in qualifying revenue either.

As if things can’t get more uncertain for a business owner trying to figure the revenue decline test, there is an anti-abuse measure which we will describe below that may deny the entire CEWS claim, with an additional 25% penalty, if the employer takes any action or participates in any transaction or event that has the effect of reducing March to May 2020 revenues.

What an ‘extraordinary’ mess. Given the government’s language on “cheating the system” with reference to claiming CEWS, we are very concerned that there will be significant CRA audit activity in the near future, despite the legislation being very confusing to many business owners. [Note to ourselves: beef up Moodys’ tax litigation team for the aftermath 😉].

Now, some good news on the determination of qualifying revenue. It appears the Department of Finance listened to the tax community (and maybe our blog), and adapted the revenue decline test to complex corporate group situations. For organizations with multiple entities, the entity that employs people may not actually be the entity that earns revenue from customers. Since qualifying revenue excludes amounts derived from non-arm’s length persons (non-arm’s length generally means a close relationship), there were concerns that the revenue decline test would not be applied properly in those situations. To tackle this, the Bill provides several special rules – laid out in new subsection 125.7(4) – for multi-enterprises, such as:

- All members of an affiliated group (affiliation generally means common control by a person or spouse) may jointly elect to use the same consolidated qualifying revenue for the revenue decline test;

- Where an employer entity receive substantially all (typically means 90% or more) of its revenue from non-arm’s length persons, a joint election may be made to calculate the employer’s decline in revenue based on the non-arm’s length person’s decline in revenue. A complicated formula is involved.

- Alternatively, a group that normally prepares consolidated financial statements may choose to determine qualifying revenue separately for each member, but every member of that group must do the same.

One of the FAQs below provides an example to illustrate these complicated, but generally effective, multi-enterprise rules.

How is the amount of CEWS for each Claim Period determined?

Employers must apply for all of its CEWS entitlement before October 2020 – this is part of the definition of “qualifying entity”. CEWS is calculated based on “eligible remuneration” paid to an “eligible employee” in respect of a week in a Claim Period.

Eligible remuneration

“Eligible remuneration” – defined in new subsection 125.7(1) – can include salary, wages, commissions and other remuneration like taxable benefits, but it does not include severance or stock option benefits. For some reason, the government’s webpage on CEWS mentions that the taxable benefit from personal use of corporate vehicle cannot qualify for CEWS. We do not see any exclusion of such benefits in the actual legislation.

Eligible employee

An “eligible employee” – defined in new subsection 125.7(1) – means an individual employed in Canada by the employer in the Claim Period, other than an individual who is without remuneration by that employer in respect of 14 or more consecutive days in the Claim Period. In other words, if the employer has not paid any wages (or other remuneration) to that employee in respect of 14 or more consecutive days in a Claim Period, the employee is not an “eligible employee” and any wages the employer does pay in respect of the rest of the same Claim Period do not qualify for CEWS. This seems to be an imperfect measure to prevent the government from having to pay the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (“CERB”) to the employee while paying CEWS to the employer for part of the same four-week period. However, it also appears to prevent an employer from claiming CEWS for some new employees initially.

For example, let’s assume an employer (Krusty Krab) hires a new employee (Patrick) on April 26, 2020 and then applies for the CEWS for Claim Period 2 (April 12 to May 9, 2020) in respect of the wages it paid to Patrick for April 26 to May 9, 2020. Krusty Krab will not be allowed to do so, since there were 14 or more consecutive days in Claim Period 2 for which Patrick was “without remuneration” by Krusty Krab. Contrast this with another employee (Spongebob) whom Krusty Krab hired on April 25, 2020. Spongebob was only without remuneration by Krusty Krab for 13 consecutive days in Claim Period 2, being April 12 to April 24, 2020. Therefore, Spongebob is an eligible employee and Krusty Krab gets CEWS for the wages it paid Spongebob during Claim Period 2, from April 25 to May 9, 2020.

In this scenario, both Patrick and Spongebob could have applied for CERB, but the employer is denied the CEWS for only one of them. Treating Spongebob and Patrick differently just because Spongebob – being Spongebob – is a keener and started one day earlier with Krusty Krab than Patrick appears to be an unintended consequence of these rules.

The government FAQ (#14) confirmed rumors that the CRA will allow employers to retroactively hire employees and pay them retroactively to qualify for additional CEWS. While this is now clearly allowed from the CEWS perspective, we caution employers to seek legal advice from experts in employment law when considering retroactive hiring/pay. Also, the employees will be required to return or repay CERB if the retroactive hiring disqualify them from CERB.

Wage subsidy calculation for different categories of employees

After determining what eligible remuneration has been paid to eligible employees, what’s next? The employer needs to then separate those eligible employees into two categories:

- Arm’s length eligible employees hired on March 16, 2020 or after, and who were never an employee of the employer at any time between January 1 and March 15, 2020; and

- (i) Non-arm’s length eligible employees, or (ii) arm’s length eligible employees who were employees of the employer at any time between January 1 and March 15, 2020.

Who are non-arm’s length employees? Generally speaking, that is an employee who controls the employer, is related to someone who controls the employer, or who acts in concert with a common interest with the employer. See CRA’s Folio for an explanation of non-arm’s length relationship.

New arm’s length employees

For arm’s length employees hired on March 16, 2020 or after and who was never an employee of the employer between January 1 and March 15, 2020, the CEWS amount for each week in the Claim Period will be 75% of the eligible remuneration paid to the eligible employee in respect of that week, up to $847 per week.

- Example: Sandy is a new employee of Krusty Krab who started on March 16, 2020, with a weekly salary of $1,200. Sandy is an eligible employee who deals at arm’s length with Krusty Krab. Since 75% of $1,200 is $900, which exceeds $847, Krusty Krab will receive $847 for each week in Claim Period 1 with respect to Sandy provided that Krusty Krab meets the revenue decline test.

While this sounds simple, there may be complications in practice. What if Sandy is paid a salary once a month and due to seasonality of the work does most of her work during the last two weeks at the end of each month, can the CRA argue that most of her monthly pay was “in respect of” the latter weeks of the month and thus wages that were “in respect of” the first two weeks were insufficient to qualify for the full $847 per week? Sound far fetched? Alternatively, what if Sandy is paid solely by commissions on realized sales, and she only made sales on a certain week but not on other weeks – would CEWS be applicable only for the commission-earning week but not the other weeks?

Pre-existing arm’s length employees

For arm’s length employees who were employees of the employer at any time between January 1 and March 15, 2020, the CEWS amount for each week in the Claim Period will be equal to the greater of:

(a) the least of

- 75% of eligible remuneration paid to the eligible employee in respect of that week;

- $847

(b) the least of:

- 100% of eligible remuneration paid to the eligible employee in respect of that week;

- 75% of “baseline remuneration” in respect of the eligible employee; and

- $847

An eligible employee has “baseline remuneration” – as defined in subsection 125.7(1) – only if she or he received remuneration from the employer at any time between January 1, 2020 and March 15, 2020. Baseline remuneration is equal to that person’s average weekly eligible remuneration during that period but excluding any period of 7 or more consecutive days for which the employee was not remunerated.

The rationale behind the mechanics of the baseline remuneration is that due to the COVID-19 crisis, some employers have reduced wages for some existing employees (or laid off employees, then hired them back at reduced wages). Part (b) of this rule ensures that the CEWS takes into account the employee’s pre-crisis remuneration when calculating the 75% subsidy amount.

- Example 1: Plankton started working for Krusty Krab on January 12, 2020, for a weekly wage of $600 per week. Plankton took an unpaid 7-day vacation during February 16 to 22, 2020. From February 23 to March 15, 2020, his weekly wage was reduced to $500 per week. After March 16, 2020, Krusty Krab further reduced Plankton’s salary to $450 per week.

In determining Plankton’s baseline remuneration, we would ignore any period of 7 or more consecutive days for which he wasn’t remunerated. This means ignoring the days prior to him starting work on January 12 and ignoring the unpaid 7-day period between February 16 to 22. After removing those periods, Plankton had following paid weeks between January 1, 2020 and March 15, 2020:

- 5 weeks of $600 per week

- 3 weeks of $500 per week.

A reasonable approach to determine Plankton’s average weekly eligible remuneration for those 8 weeks is: ($600 x 5/8) + ($500 x 3/8) = $562.50. $562.50 is Plankton’s baseline remuneration.

For Claim Period 1 (March 15 to April 11, 2020), assuming Krusty Krab meets the revenue decline test for the Claim Period, it can apply CEWS for Plankton’s wages paid in respect of the weeks within Claim Period 1, equal to the greater of:

(a) the least of:

- 75% of remuneration to Plankton for each week- 75% x $450 = $337.50 per week;

- $847 per week.

(b) the least of:

- 100% of remuneration to Plankton for each week- $450 per week;

- 75% of Plankton’s baseline remuneration – 75% x $562.50 = $421.88 per week;

- $847 per week.

Since the least of (a) is $337.50 per week and the least of (b) is $421.88 per week, the greater of the two is $421.88 per week. Therefore, Krusty Krab gets $421.88 per week of CEWS for the $450 per week wages it pays Plankton during Claim Period 1.

- Example 2: In compliance with the government’s encouragement for employers to make their best effort to increase their employee’s remuneration to pre-crisis level, Krusty Krab decided to increase Plankton’s salary back to $600 per week starting April 12, 2020.

Plankton’s baseline remuneration is still $562.50, as that figure was based on January 1 to March 15, 2020 remuneration. Therefore, the CEWS computation for Claim Period 2 (April 12, 2020 to May 9, 2020) for wages paid to Plankton will be the greater of:

(a) the least of:

- 75% of remuneration to Plankton for each week- 75% x $600 = $450 per week;

- $847 per week.

(b) the least of:

- 100% of remuneration to Plankton for each week- $600 per week;

- 75% of Plankton’s baseline remuneration – 75% x $562.50 = $421.88 per week;

- $847 per week.

Since the least of (a) is $450 per week and the least of (b) is $421.88 per week, the greater of the two is $450 per week. Therefore, Krusty Krab gets $450 per week of CEWS for the $600 per week wages it pays Plankton during Claim Period 2.For arm’s length employee, increasing remuneration after March 15, 2020 will increase the amount of CEWS entitlement (up to the $847 per week maximum per employee).

Non-arm’s length employees

The mechanics of the CEWS calculation for non-arm’s length employees is the same as those for pre-existing employees, except that the computation is restricted to the (b) component described above, i.e. the CEWS for wages paid to a non-arm’s length employee is

(b) the least of:

- 100% of eligible remuneration paid to the eligible employee in respect of that week;

- 75% of “baseline remuneration” in respect of the eligible employee; and

- $847

By limiting CEWS for non-arm’s length employee to this (b) component, CEWS entitlement cannot be increased by increasing wages paid to non-arm’s length employees after March 15, 2020. While the baseline remuneration works as a relieving provision for pre-existing employees who had their wage reduced (because it allows CEWS to be calculated on the higher pre-crisis wages), the baseline remuneration standard serves as a policing tool for non-arm’s length employees. It prevents businesses from adding family members as employees or artificially inflating their wages for the sake of obtaining CEWS.

- Example: Eugene Krabs is the 100% owner of Krusty Krab. Eugene had always paid himself $500 per week. After seeing the headline of Moodys’ CEWS blog on April 13, 2020 (without reading the blog closely), Eugene increased his wage to $1,129.33 per week and added his daughter, Pearl, on as an employee also at $1,129.33 per week. Since Eugene controls Krusty Krab and Pearl is related to Eugene, both of them are non-arm’s length employees of Krusty Krab.

When Eugene applies for CEWS, he was disappointed to find out that Krusty Krab’s CEWS claim for himself and Pearl will be limited to their baseline remuneration. For wages paid to Eugene and Pearl, Krusty Crab is entitled to the least of:

- 100% of remuneration paid to Eugene and Pearl for each week: $1,129.33 and $1,129.33;

- 75% of Eugene’s and Pearl’s baseline remuneration: 75% of $500 = $375 for Eugene, and 75% of $0 for Pearl; and

- $847 for Eugene, and $847 for Pearl.

Since the least of those three amounts is $375, $375 per week is the maximum CEWS Krusty Krab can claim in respect of wages it paid to Eugene and Pearl. Additionally, Krusty Krab may be denied deduction of the wages it pays to Pearl under either section 67 or paragraph 18(1)(a) of the Act if those wages are not considered reasonable.

Other adjustments to the CEWS amount

Further adjustments to the CEWS amount are provided for in new subsection 125.7(2):

- The CEWS is reduced by the employer’s entitlement to any 10% wage subsidy for the same Claim Period;

- The CEWS is reduced by any amounts received by EI work-sharing benefit received by employees for the same Claim Period; and

- The CEWS is increased by 100% of the employer-portion of CPP and EI for eligible employees who are “on leave with pay”. The CRA considers an employee to be on leave with pay if that employee is remunerated by the employer but does not perform any work for the employer. This part of the CEWS is not limited by the $847 per week cap, but the employer still has to first make all the required payroll withholding and remittance and then apply for CEWS to get back the employer-portion of CPP and EI.

Legal nature of the CEWS

The CEWS amount will be credited to the employer as an overpayment of income tax for year 2020. The legislation provides that even if the employer has overdue income tax or GST/HST obligations, the Minister may still refund this deemed overpayment to that employer and at any time pursuant to new subsection 164(1.6) of the Act.

The legislation also clarifies that the CEWS is considered government assistance. This means that the CEWS amount is taxable to the employer under paragraph 12(1)(x) of the Act.

The government FAQ (#31) stated that CRA has the discretion to withhold CEWS payments in cases where there is a significant history of not complying with a duty or obligation under Canada’s tax laws. Hopefully, none of our readers fall into this category of taxpayers.

How do the rules prevent abuse?

Let’s face it. A program that gives out money fast and furious can be subject to bad actors trying to take advantage. To protect the integrity of the CEWS program, the Bill included many anti-abuse measures:

- Any inappropriate CEWS claim must be repaid by the employer;

- The legislation requires that the entity applying for CEWS had a payroll number with the CRA on March 15, 2020. This prevents entities that never had employees before the crisis from now hiring employees to claim CEWS. Many small owner-manager businesses in Canada unfortunately have never applied for a payroll number because the owner pays themselves through dividends – for them, they cannot qualify for CEWS;

- The legislation requires the individual who has principal responsibility of the financial activities of the employer to attest to the completeness and accuracy of the CEWS application – see below discussion on fines and imprisonment for false attestation;

- Eligible remuneration excludes any amount paid to an employee that can reasonably be expected to be returned, directly or indirectly in any manner whatever, to the employer or someone not dealing at arm’s length with the employer. This exclusion obviously attempts to prevent artificially increasing remuneration so as to claim an increased CEWS amount;

- Eligible remuneration also excludes any amount paid to an employee that exceeds that employee’s baseline remuneration, if it is reasonably expected that after the Claim Period the employee will be paid a lower weekly amount than their baseline remuneration, and one of the main purposes for this arrangement is to increase the employer’s CEWS entitlement.

- If the same employee is employed in a week by two or more employers who do not deal at arm’s length with each other, the total CEWS cannot exceed the CEWS entitlement that would arise if only one employer had paid all of that employee’s remuneration for that week. In other words, a business cannot double-up on the $847 cap by simply dividing up an employee’s salary into the payroll of two or more internal entities.

- If the employer or a non-arm’s length person enters into a transaction, participates in an event, or takes an action that has the effect of reducing qualifying revenues for March, April or May 2020 (other than choosing between the multi-enterprise rules or choosing between cash vs accrual method as described earlier), and one of the main purposes of such transaction / event / action is to qualify for the revenue decline test, the entire CEWS application of the employer for the Claim Period is denied pursuant to new subsection 125.7(6). Additionally, the employer will be assessed a penalty of 25% of the CEWS applied for pursuant to new subsection 163(2.901).

- A person who knowingly, or under circumstances amounting to gross negligence, has made or has participated in, assented to or acquiesced in the making of, a false statement or omission in a CEWS application is subject to a penalty of 50% of the inappropriate amount being claimed pursuant to amendments made to subsection 163(2).

- The Minister may communicate to the public, in any manner the Minister considers appropriate, the name of any persons who submit a CEWS application pursuant to new subsection 241(3.5) of the Act. This is likely a “name and shame” mechanism for employers whom the government considers to not have acted honourably, including those who may found ways to skirt the anti-abuse measures described here. This may include those businesses who did not use the CEWS money in an intended manner or did not make a good faith attempt to return employees’ wages back to pre-crisis level (which was a requirement in the government’s previous announcements). In our view, this is going too far and gives the CRA far too much power to name and shame taxpayers who may have inadvertently made a mistake, was not convicted in Court of an offence, etc.

Although not amended by the Bill, existing subsection 239(1.1) of the Act will likely cover an employer making a false or deceptive attestation in the CEWS application. This is a criminal offence potentially resulting in up to 200% of the improper CEWS claim and 2 years of jail for the attestor.

Note that the regular general anti-avoidance provision (the GAAR) – under section 245 of the Act – should be also applicable to a misuse or abuse of the CEWS legislation. That is because the GAAR applies to transactions that increase a refund or other amounts under the Act.

2020 Year-End T4 Reporting Requirement

Whether an employer receives CEWS has absolutely no bearing on the employee’s tax treatment of wages received. Wages received is included in the employee’s taxable income, period. The government FAQ (#29) states that employers will be required to report on each T4 slip to their employees the amount of CEWS the employer received in respect of that employees’ salaries during the year. Since CEWS does not impact the tax treatment to the employee, there is no tax technical reason behind this reporting. Our guess for the government’s rationale behind this reporting requirement is to prevent fraudulent claims for ‘ghost’ employees. Every employee whom the employer has claimed CEWS on will know how much CEWS the employer received in respect of their wages, and it will be readily apparent to the employee if they have not actually been paid an amount of wages that justify the amount of CEWS received by their employer on their wages. Also, the CRA’s system can easily compare the employer’s CEWS claimed to the total CEWS reported on all T4 slips issued for the year by that employer. At the same time, this may be a tool for CRA to identify inappropriate CERB claims by an employee.

Additionally, this T4 reporting has the political benefit of letting employees know that their wages have been subsidized by the current government.

FAQs on the Revenue Decline Test

Is the revenue decline test based on profit or gross revenue?

The revenue decline test compares the qualifying revenue of the current reference period (March to May 2020) to the qualifying revenue of the prior reference period (March to May 2019, or an average of January / February 2020 under the alternative method). The term “qualifying revenue” means the inflow of cash, receivables or other consideration arising in the course of the ordinary activities of the eligible entity — generally from the sale of goods, the rendering of services and the use by others of resources of the eligible entity — in Canada in the particular period.

Therefore, qualifying revenue refers to top-line / gross revenues, not profit. Expenses should be irrelevant in applying the revenue decline test.

If the employer’s revenue decline turns out to be slightly off what is required under the revenue decline test, is there partial entitlement to CEWS?

No. Based on the rules announced, the revenue decline is an all-or-nothing test. For example, assume the employer has applied for and received CEWS for Claim Period 1 (March 15 to April 11, 2020), and it is later determined by the CRA that its March 2020 revenue was 14% lower than March 2019 revenue (assuming it did not elect to use the alternative method of comparing to January / February 2020 revenue). Because the required 15% reduction for Claim Period 1 is not met, the employer will be required to repay all CEWS received in respect of Claim Period 1. Additionally, if the employer relied on the deeming rule in 125.7(9) for Claim Period 2 due to it thinking that it met the revenue decline test in Claim Period 1, its Claim Period 2 CEWS claim will fail as well, unless it can prove the required 30% revenue decline for Claim Period 2.

Does the decline in revenue need to be related to COVID-19?

No, nothing in the legislation or the government’s announcements indicate this as a requirement.

Does the employer need to submit monthly financial statements with its application each month?

It does not appear so. In applying for the subsidy, an employer would be required to attest that it met the decline in revenue test. The employer is required to keep records demonstrating the reduction in gross revenues and remuneration paid to employees. We anticipate that the CRA will have audit programs after-the-fact to audit CEWS applicants’ eligibility. An obvious audit tool to the CRA would be to compare monthly revenues based on monthly GST filings for monthly filers.

Does it matter which accounting standards the employer follows (e.g. IFRS, ASPE, US GAAP, etc.)?

No, it appears that as long as the employer is applying a consistent accounting standard that it had used pre-crisis, it should be considered as its “normal accounting practices”. The purpose of this requirement is likely to prevent easy manipulation of the 2020 revenue number. In other words, the government does not want employers switching to an accounting method that shows lower revenue for the March to May 2020 periods in order to meet the revenue decline test. If the accounting standard in these months are indeed different than the same months in 2019, be prepared to later explain to the CRA why the accounting standard being employed is the “normal accounting practices”.

Note that the Bill contains numerous exceptions to the normal accounting practices rule, particularly in the context of consolidated revenues between affiliated groups and the use of the cash accounting method.

Is revenue net of bad debts? In other words, if the employer issues an invoice in April 2020 to a customer who refuses to pay, is that invoice amount included in April 2020 even though the employer cannot (and may never) collect?

Our general understanding is that most conventional accounting practices classify uncollectible invoices as an expense item (bad debt expense), and not an offset against revenues. [Warning: although some of the authors are accountants, we, unlike our colleagues at Moodys Private Client LLP, have not practiced accounting for years since the sole focus of our work is tax].

However, even though bad debt expenses may not offset revenues, companies may elect an election under paragraph 125.7(4)(e) of the Act to use the cash method of accounting in determining if there was a decrease in qualifying revenue. Under the cash method, that unpaid invoice will not be part of the qualifying revenue in April 2020. However, if the election is made, the company must be consistent in using the cash method for all Claim Periods (including the previous March period).

Does revenue for a professional firm – like an accounting or law or consulting firm – need to include work-in-progress in the computation of qualifying revenues?

Though it is not clear, probably yes where WIP has been included in revenue under the firm’s normal accounting practices. It is safer to rely on the cash accounting method election if work-in-progress (WIP) makes or breaks the revenue decline test.

On the one hand, WIP does not appear to be described in the definition of qualifying revenue, which “…means the inflow of cash, receivables or other consideration arising in the course of the ordinary activities…”. WIP is not cash, receivables, and we do not believe that WIP is “other consideration”.

However, given the inflow of cash, receivables or other consideration language is a parroting of ASPE definition of revenue, perhaps the answer simply is that if WIP was included in revenue under the employer’s normal accounting practices, then it should be included in qualifying revenue. Interestingly, prior to 2017, many (probably most) professional firms did not account for WIP in their revenues due to section 34 of the Act. However, an amendment of section 34 has since required the inclusion of WIP into taxable income – see our blog on this. Because of that, many professional firms have switched their accounting methods to include WIP in revenues. Firms that have done so are likely required to include WIP in qualifying revenue for the purpose of the revenue decline test.

In any case, the cash method accounting election can be used to exclude WIP. Note that if a professional services firm intentionally delays billing WIP so as to reduce qualifying revenues in a current period then the anti-abuse rule in subsection 125.7(6) might apply to deny CEWS benefits and apply the applicable penalties.

Qualifying revenue excludes “extraordinary item” – what does that mean?

Since the legislation does not provide any definition of that term, this will be based on what is an extraordinary item under the employer’s “normal accounting practice”. This will be a gray area for many businesses and likely an area of future dispute between claimants and the CRA. Everything that is happening now due to COVID-19 appears to be an “extraordinary item” to us…

Does Qualifying Revenue include revenue from non-arm’s length sources?

The Bill provides that qualifying revenue excludes amounts derived from persons or partnerships not dealing at arm’s length with the employer. See our earlier discussion.

The employer’s sole source of revenue is from providing services to a company owned by the father of the owner of the employer. Can the employer qualify for CEWS?

The Bill provides a potential exception where a company may qualify for CEWS even if its only source of income is from non-arm’s length sources. In the computation of qualifying revenue, if all or substantially all (this is a term which the CRA considers to be 90% or greater) of an employer’s revenue for a qualifying period is from persons or partnerships not dealing at arm’s length with the employer, both parties may jointly elect to apply a special formula under paragraph 125.7(4)(d) of the Act to determine if the employer will qualify for CEWS.

For example, Bob is the sole shareholder of a corporation (Son Co) that provides management services to a corporation owned by Bob’s father (Dad Co). Management fees from Dad Co are Son Co’s only source of income. During March 2019, Son Co earned $500 in management fee revenue, and Dad Co had $2,000 in revenue. During March 2020, Son Co continued to earn $500 in management fee revenue from Dad Co, but Dad Co had only $1,000 in revenue. In looking at whether Son Co would qualify for CEWS, Son Co would fail the revenue decline test under the normal CEWS rules because non-arm’s length revenues are ignored.

However, Son Co and Dad Co may choose to elect under paragraph 125.7(4)(d) of the Act. If that is the case, paragraph 125.7(4)(d) deems Son Co’s qualifying revenue for the prior reference period (March 2019) to be $100. Then, the paragraph deems Son Co’s current reference period (March 2020) to be the amount under the following formula:

$100 (A / B) (C / D) where:

A= Son Co’s qualifying revenue including income from non-arm’s length sources for the current period earned from a particular non-arm’s length person or partnership;

B= Son Co’s qualifying revenue including income from non-arm’s length sources for the current period earned from all non-arm’s length person or partnership;

C=the particular non-arm’s length parties’ (Dad Co) qualifying revenue for the current period;

D= the particular non-arm’s length parties’ (Dad Co) qualifying revenue for the prior reference period.

Therefore, Son Co’s March 2020 qualifying revenue would be calculated as:

$100 (500 / 500) (1000 / 2000) = $50.

Since Bob Co’s qualifying revenue for March 2019 is deemed by paragraph 125.7(4)(d) to be $100, and its qualifying revenue for March 2020 is deemed by the same to be $50, Son Co would be considered to have suffered a 50% decline and will qualify for CEWS for Claim Period 1. Also, because of the deeming rule in subsection 125.7(9), it automatically meets the revenue decline test for Claim Period 2 as well.

Does my US Subsidiary income matter in my qualification for CEWS in Canada?

Assume the following facts:

BobCo, a Canadian corporation, formed a wholly owned US subsidiary in 2019 (“USCo”) which carries on business in the US BobCo manufactures products and has employees in Canada. It sells its products mostly to USCo (in accordance with proper transfer pricing principles!), but it also sells some products from its Canadian factory directly to arm’s length customers around the world. USCo carries on business only in the US and files US income tax returns annually.

During March 2019, BobCo sold $90 worth of product to USCo and $1 worth of product to arm’s length customers. In that same month, USCo sold $200 worth of product to arm’s length customers in the US.

During March 2020, BobCo sold $90 worth of product to USCo and $10 worth of product to arm’s length customers. In that same month, USCo only sold $100 worth of product to arm’s length customers in the US.

Unconsolidated method

Under the default method of computing qualifying revenue, BobCo is forced to ignore all non-arm’s length amounts, which means that it only counts sales to arm’s length customers. In that case, it has an increase in qualifying revenue (from $1 to $10). Although qualifying revenue only includes amounts earned in the course of ordinary activities in Canada, where a customer is located should not matter as long as the activities from which the sales derived is carried out in Canada. Since Bobco has no decline in qualifying revenue, it cannot pass the revenue decline test under this default method and therefore would not qualify for CEWS.

125.7(4)(b) consolidation election

The computation of revenue provided in paragraph 125.7(4)(b) provides that “an eligible entity and each member of an affiliated group of eligible entities of which the eligible entity is a member jointly elect, the qualifying revenue of the group determined on a consolidated basis in accordance with relevant accounting principles is to be used for each member of the group”. However, in the determination of qualifying revenue, the definition still requires that only amounts earned in the course of ordinary activities in Canada be included.

As such, even if BobCo and USCo jointly elect under paragraph 125.7(4)(b) to calculate qualifying revenue on a consolidated basis, the revenues of USCo in March 2020 and March 2019 are likely irrelevant to the qualifying revenue computation because USCo’s revenues were not derived from the course of ordinary activities in Canada. Also, asserting USCo’s revenues are from activities in Canada would be contrary to historical filing positions that USCo only carried on business in the US and not in Canada – if it did carry on business in Canada, USCo would have been obligated to at least file a ‘treaty-based’ tax return to the CRA. Therefore, even if the consolidated method under 125.7(4)(b) is followed, BobCo cannot rely on the drop of USCo’s revenue in the revenue decline test. With the USCo’s revenue excluded from consolidated qualifying revenue, there is no decline (consolidated qualifying revenue increased from $1 to $10) and BobCo cannot meet the revenue decline test.

125.7(4)(d) consolidation election

Under paragraph 125.7(4)(d), there is the possibility that BobCo would indeed qualify for CEWS. If all or substantially all(interpreted by the CRA to be 90%) of the revenue of an employer during a Claim Period is from one or more particular persons or partnerships which it does not deal at arm’s length, a formula is used to determine the calculation of qualifying revenue of the employer.

As BobCo does not deal at arm’s length with UsCo, and all or substantially all of its revenue is from USCo ($90 of $100 revenue), provided BobCo and USCo jointly elect, they should qualify to use paragraph 125.7(4)(d) to determine BobCo’s qualifying revenue. The calculation would then be completed the using the same formula described in the previous FAQ, where BobCo is deemed to have $100 of qualifying revenue in March 2019, and its March 2020 qualifying revenue is calculated as:

$100 (A / B) (C / D)

A= BobCo’s qualifying revenue from non-arm’s length sources, being UsCo in the current period ($90);

B= The total revenue from all sources of BobCo from non-arm’s length sources ($90);

C= the particular person or partnership’s qualifying revenue (determined as if the definition of qualifying revenue in subsection (1) were read without reference to “in Canada”)) for the current reference period. This is where the calculation turns- as the qualifying revenue of the non-arm’s length source does not need to be in Canada. As a result, UsCo has $100 of qualifying revenue during March 2020.

D=the particular person or partnership’s qualifying revenue (determined as if the definition of qualifying revenue in subsection (1) were read without reference to “in Canada”)) for the prior reference period (USCo has $200 of qualifying revenue during March 2019).

As a result, the calculation would be = $100(90/90) (100/200) = $50

Therefore, BobCo will have qualifying revenue of $50 in the current reference period, and $100 in the past reference period, and as a result there is a 50% drop which would qualify BobCo for Claim Period 1. Note that the increase in Bobco’s arm’s length sales from March 2019 to March 2020 has no bearing on this calculation.

It is important to note that this provision only applies if all or substantially all of the revenue is from a non-arm’s length source. If BobCo had earned $30 of income from arm’s length sources and only $70 from USCo and other non-arm’s length sources, it would not be allowed to take advantage of paragraph 125.7(4)(d).

Given the Claim Periods straddle the months being tested, how can employers be sure they will meet the revenue decline test for the month while they are paying their employees during the month?

As subsection 125.7(9) of the Act will deem an entity to qualify for the CEWS in the Claim Period immediately following the Claim Period the entity originally qualified in, an entity may know that it will qualify in the following month if they otherwise qualify in the current month. For example, assume a business has a 20% decline in “qualifying revenue” for March 2020 compared to March 2019. This would mean the business already knows that it is eligible for CEWS for Claim Period 1, and that it will be deemed to qualify for Claim Period 2. Going into May, if the business knows it had a 32% revenue decrease in April, it should be deemed to qualify for Claim Period 3 as well. This helps provide some certainty in advance for a business owner as they may not need to “predict” their future revenue unlike previous versions announced by the government.

A business group’s financial statements are prepared as a consolidated group, can we calculate qualifying revenue for CEWS on a consolidated basis for some entities but not others within the same Claim Period?

No. According to paragraphs 125.7(4)(a) and (b), if a business is part of a group of other employer entities that normally prepares consolidated financial statements, the businesses must either determine their qualifying revenue on a consolidated basis as an entire group, or each member must determine its qualifying revenue separately.

Are a group of entities permitted to switch between consolidation basis and non-consolidated basis of determining qualifying revenue from one Claim Period to the next?

Yes. Paragraphs (a) to (e) of subsection 125.7(4) sets out the various elected methods for determining qualifying revenue. Only paragraph (e) – electing to determine qualifying revenue on a cash basis – requires that the same election be applied across all Claim Periods. Paragraphs (a) to (d) provides for consolidation / non-consolidation approaches for different situations, but with no requirement that the same approach be used across different Claim Periods. Given this clear distinction in wording within the same subsection of the legislation, it appears to us that the legislation intended for a CEWS claimant to be able to elect to determine qualifying revenue on a consolidated basis for their group of entities for one Claim Period, and be free to choose to determine qualifying revenue on non-consolidated basis for all entities in a different Claim Period.

Are sales of capital property included in qualifying revenue?

As we discussed above, this may create future disputes between the CRA and taxpayers. The Department of Finance webpage clearly states that amounts on account of capital are excluded, but this is not clear at all in the Bill. Although we believe proceeds from sale of capital properties will be excluded as they should not be part of the ordinary business activities of the business, we find it surprising this was not clearly indicated in the legislation, even on a “for greater certainty” basis.

If a business qualifies for March, does it need to qualify for April and May Claim Periods?

If a business qualifies for March by having a 15% decrease in revenue, they will be automatically deemed to qualify for the April Claim Period. However, the business will need to re-qualify for the May Claim Period, by having a 30% decrease in qualifying revenue during that Claim Period.

What do I need to do to “elect” to use the January and February 2020 as a reference period?

As it reads from the Bill, an entity does not need to provide any explanation to CRA to use the alternative reference period. Once an entity decides to use the alternative reference period, it must continue to do so for all Claim Periods.

If a business’ revenue is from subscription services, or royalty fees, are these amounts included in the calculation of qualifying revenue?

The legislation provides that qualifying revenue includes amounts from “the use by others of resources of” the employer. Therefore, qualifying revenue includes the use of property of a company by others for a fee (such as a subscription fee for use of a company’s property).

Does it make sense for me to wait to apply for CEWS after I have determined monthly revenues for March, April, and May 2020?

Businesses may apply as soon as the portal is open for registration (April 27, 2020). However, if a business is not cash strapped, it may actually be advantageous to wait to apply for CEWS. In order to be a “qualifying entity”, an employer need only file an application for CEWS in respect of a qualifying period before October 2020. As there are situations in which an employer may elect – such as choosing between January 2020 and February 2020 revenue versus the corresponding month of the 2019, or for choosing cash accounting versus normal accrual accounting, an employer may actually wait until these periods are over to determine which elections are advantageous to the company in order to maximize CEWS benefits (if for example, choosing cash accounting would cause the company to not qualify for May 2020). The company will have the benefit of hindsight when filing for CEWS, provided it applied prior to October 2020.

Furthermore, according to paragraph 125.7(5)(a) of the Act, the CEWS amount will limited to the amount claimed in the application. In other words, it appears to us that you may only get one chance to get it right. If the extra time can be taken to get it right, it may be prudent to take that extra time.

What if a business’ revenue decline is close to the required 15% or 30% to qualify for CEWS, and takes steps to further reduce revenue such as limiting store hours or dropping prices (as they determined that obtaining the CEWS benefit is better than maintaining the revenue above the required decline %)?

Subsection 125.7(6) provides anti-abuse rules that will deem the qualifying revenue for a current period to be equal to the qualifying revenue of the prior period (resulting in an entity not meeting the revenue reduction test) if the eligible entity enters into a transaction or participates in an event (or a series of transactions or events) or takes an action (or fails to take an action) that has the effect of reducing the qualifying revenues of the eligible entity for the current reference period, it is reasonable to conclude that one of the main purposes of the transaction, event, series or action is to cause an eligible entity to qualify for CEWS.

As this legislation is quite broad, it may be possible that these actions (such as dropping price) could cause an entity to not qualify for CEWS, if the CRA asserts that one of the main purposes was to reduce revenue to qualify for CEWS.

If a business elects to use cash accounting, do they need to recalculate the prior reference period using the cash accounting methodology as well?

The legislation, as it is written, is unclear if an entity makes the election for all qualifying periods (being March, April, and May 2020), if they are forced to recompute revenue for the prior reference period (being March, April and May 2019, or the average of January / February 2020) using the cash accounting methodology as well. We think the better interpretation is that the election impacts the determination of qualifying revenue for both the current reference period and the prior reference period. Therefore, if you elect under cash method, you will be comparing between cash method prior period to cash method current period.

We hope there will be further clarity from the CRA on this important question.

FAQs on Other Aspects of CEWS

What is the maximum subsidy under CEWS?

Per employee, the maximum would be $847 per week * 12 weeks (March 15 to June 6, 2020, unless the government extends the program) = $10,164. There is no maximum per employer.

Note that the subsidy is not 75% of $58,700, as commonly referred to in press releases. $58,700 is merely the annualized equivalent of the $847 per week CEWS amount ($58,700 divided by 52 weeks, multiplied by 75% = $847 weekly CEWS).

Under certain circumstances, the CEWS program will also provide 100% refund for the employer-portion of CPP and EI, in addition to the $847 per week. This is discussed in a separate Q&A below.

Do employers have to pay the 25% of salary not covered by CEWS?

Generally, yes. Unless there was a wage reduction after March 15, 2020 for the particular employee, the CEWS is calculated based on salary paid for the week. Therefore, the employer needs to have first paid at least the CEWS, grossed up by 75%, to the employee in order to obtain the CEWS amount. For example, for an employee whose wage is $1,000 per week, the employer has to pay that $1,000 to the employee (with the normal payroll withholdings) and then apply for CEWS of $750.

For situations involving an employee whose wage has been reduced after March 15, 2020, the CEWS would be calculated based on both the baseline remuneration and the current remuneration. In some circumstances, the CEWS could even cover 100% of the weekly pay. See the example with Krusty Krab and Plankton earlier.

Will salaries paid to a non-arm’s length employee be eligible for CEWS?

Yes. However, non-arm’s length employees must have a “baseline remuneration” in order to be eligible for CEWS. Wages paid to non-arm’s length employees who do not receive regular employment income payments (more specifically, was not paid any salary or wages between January 1 to March 15, 2020) may not qualify for CEWS. See the example with Krusty Krab, Eugene Krabs and Pearl earlier.

Are wages paid to new employees hired during the crisis eligible for CEWS?

Yes, if the new employee is arm’s length with the employer. New non-arm’s length employees will not be eligible for CEWS.

The pay period for our employees does not line up with the Claim Period. Do I only claim wages I actually paid out during the Claim Period?

We are so disappointed that the government did not use their FAQ to clarify this, as this is the most common question we get from businesses and accountants. This is what the legislation says to calculate the CEWS on: “eligible remuneration paid to the eligible employee in respect of that week” in the Claim Period.

While the remuneration needs to have been “paid”, the legislation does not specify that the payment has to occur during the week or during the Claim Period. What is relevant is that the remuneration was paid “in respect of that week”. If an employer pays monthly wages on March 31, 2020, and the next one on April 30, 2020, an employer will need to determine CEWS for Claim Period 1 (March 15, 2020 to April 11, 2020). We believe the correct method is to reasonably identify the portion of the March 31, 2020 pay and the April 30, 2020 pay that relate “in respect of” the weeks during Claim Period 1 (March 15, 2020 to April 11, 2020).

I laid off many of my employees because I could not afford them, even though there is still some work for them to do. Should I hire them back to come to work at a rate that is fully subsidized by the government?

As discussed above, the employer can hire the employees back and pay them $847 per week. As long as $847 is less than 75% of the employees’ baseline remuneration (i.e. their average weekly remuneration between January 1, 2020 and March 15, 2020), the employer may qualify for CEWS of $847 per week thus covering the entire remuneration – provided the employer meets the revenue decline test.

However, this is still a business decision. The business is still liable for the full payroll costs (including employer portion of CPP and EI), the additional income tax arising from the receipt of the subsidy (which is taxable to the business). Also, it may be subject to “naming and shaming” by the government if it did not make its “best efforts” to top up the employees to their pre-crisis remuneration level. Moreover, the business must have the cashflow to front the full payroll and associated costs before receiving the CEWS which may not be available until the middle of May.

Note that there are restrictions on claiming CEWS in a Claim Period in respect of employees who have been without remuneration for more than 14 days. See our earlier example with Patrick and Spongebob.

Note also that there are additional benefits for employees who are on leave with pay (i.e. not asked to report to work). See the below Q&A for details.

I laid off many of my employees because I could not afford them, and I have no work for them to do. Should I hire them back and keep them at home on leave with pay, at a rate that is fully subsidized by the government?

In this case, not only can the weekly remuneration be fully subsidized by CEWS, but the CEWS will also provide a 100% refund for the employer portion of CPP and EI, with no maximum overall limit. To qualify for this refund, the employee must be on leave with pay throughout a week, meaning that the employee is paid by the employer but does not perform any work for the employer throughout the whole week.

The CEWS and the refund of CPP/EI will still be taxable to the employer, and the employer may still be ‘named and shamed’ if it did not make its “best effort” to top up employees to pre-crisis remuneration level. Again, note that there are restrictions on claiming CEWS in a Claim Period in respect of employees who have been without remuneration for more than 14 days.

Does the CEWS subsidy apply to contractors?

No. The subsidy will only apply to employee remuneration. In order to remedy this, businesses might be able to terminate existing contractor relationships and hire those arm’s length contractors back as new employees and obtain the subsidy, provided the business has an existing payroll account with the CRA as of March 15, 2020. There are no specific rules in the legislation that would prevent this type of arrangement, provided the contractor deals at arm’s length with the employer and there was no previous employment relationship that created baseline remuneration. Will this be considered abusive under the GAAR? It would seem sensible that if a contractor deals at arm’s length with a corporation, terminating the contractor relationship to replace it with an employment relationship should not be considered abusive.

Can I claim both the 10% subsidy and the CEWS?

Yes, but the amount of the 75% CEWS subsidy the employer receives will be reduced by the amount of the 10% subsidy during the same Claim Period. We recommend immediate reduction of payroll remittance to reflect the 10% subsidy if you qualify. More specifically, the 10% subsidy is claimed by a reduction in income tax remittance, up to $1,375 per employee and $25,000 for all employees of that business. See our blog and the government webpage for more details on the 10% wage subsidy.

The government released Income Tax Regulations on May 13, 2020 that allows the 10% subsidy to be reduced to 0% by an election of the employer. If the employer makes this election, that would correspondingly decrease the amount that needs to be subtracted from the CEWS computation during the same Claim Period. See Q21 of the government FAQ for a numeric example.

How can employers apply for CEWS?

A portal through CRA My Business Account should be available on April 27, 2020. Employers should make sure they register for My Business Account and direct deposit with the CRA if they have not already done so in the past. The direct deposit arrangement must be set up as part of the employer’s payroll account. Even if you have previously registered, we encourage trying to log onto My Business Account to ensure you will be ready as soon as the CEWS application process is live. Also, according to the CRA, Level 2 or 3 authorized representative of a business will be able to apply on behalf of the business through the “Represent a Client” service.

If the employer pays wages to an employee (and applies for CEWS), how does this impact the employee’s ability to claim the Canadian Emergency Response Benefit (CERB)? And vice versa.

To be eligible for the CERB, the employee must involuntarily cease to work or has his or her hours reduced for reasons related to COVID-19 for at least 14 consecutive days within a four-week period and must receive less than $1,000 per month ofincome from employment (amongst certain other types of income) during those consecutive non-working days. Therefore, if the employer continues to pay wages to an employee throughout the month totalling to $1,000 or more, the employee cannot qualify for CERB.

Therefore, if the employee involuntarily ceases to work for reasons related to COVID-19 for at least 14 consecutive days and is not paid wages during those days, the employee qualifies for CERB. However, the employer may not qualify for CEWS for wages that it paid that employee during that Claim Period.

Specifically, here is the rule for employer: CEWS cannot be claimed for an employee “who is without remuneration by the [employer] in respect of 14 or more consecutive days in the [Claim Period]”. See our earlier example regarding Patrick and Spongebob.

The CRA’s FAQ (#15) makes it abundantly clear that it is the employee’s responsibility to determine their own eligibility for the CERB, and that employees need to repay or return to the government any CERB they were not entitled to. The only onus on the employer is to ensure that they do not claim CEWS for an employee who was without remuneration by the employer for 14 or more consecutive days in the Claim Period.

If a corporation who is an eligible employer amalgamates or winds-up after March 15, can its successor claim (or continue to claim) CEWS on its behalf?

The legislation does not appear to contemplate a successor corporation stepping into the shoes of a predecessor corporation. For example, since the qualification is based on a particular employer having a business number and payroll account on March 15, a successor would fail these requirements and not be able to qualify. Even if a successor corporation after an amalgamation continued to use a predecessor corporation’s business number, the successor corporation itself would not have had a business number on March 15 and would also fail the qualification requirements.

This may create some unexpected and unintended consequences for reorganizations during this crisis.

Is there personal liability for the attestation or director liability if an employer claims CEWS when it is not eligible?

There is no specific provision in the legislative amendments to attach liability to repay CEWS to a director or the person who attests in the CEWS application. A corporation that uses a false statement to claim CEWS may be guilty of an offence under subsection 239(1.1). Section 242 of the Act imputes an offence to directors, officers or agents of a corporation where a corporation has committed an offence under the Act, such as under subsection 239(1.1) of the Act. Therefore directors, officers and agents could be subject to a penalty, fine or imprisonment for a false CEWS claim, but not expressly directly liable to repay the CEWS amount.

Given that all the Canadian professional hockey teams – like the Calgary Flames, Edmonton Oilers or the Toronto Maple Leafs – had their season shut down this year, can they receive CEWS to subsidize their players’ salary?

Yes.

Related Blogs

Have you ever wondered how much your US citizenship is costing you? Why renouncing could save you hundreds of thousands and open new doors for financial opportunities.

As US expats prepare for another expensive and stressful tax filing season, we’ve compiled a list of...

Looking to make 2024 your last filing year for US taxes? Here’s what you need to do.

In a recent survey, one in five US expats (20%) is considering or planning to renounce their...

Travelling to the US? If you’re a US expat who doesn’t renounce properly, your trip may never get off the ground.

Air travel can be stressful. Rising airfares and hotel costs, flight cancellations, pilot strikes, long security wait...