Blog + News

Rely on the CRA at Your Own Peril: The (un)Availability of Equitable Remedies in the Tax Context

Introduction

The Supreme Court of Canada (“SCC”)’s recent decision in Canada (Attorney General) v. Collins Family Trust, 2022 SCC 26(“Collins”) has seemingly closed the loop on the (lack of) availability of equitable remedies in cases involving income tax.

Many taxpayers and tax practitioners are aware that one of the Canada Revenue Agency (“CRA”)’s responsibilities is to administer the Income Tax Act[1] (the, “Act”). In doing so, the CRA often provides their interpretive views on various provisions of the Act, which generally is helpful and appreciated. What is important for all to understand, however, is that the CRA is not an authority when it comes to interpreting the Act. Many tax cases at various levels of the courts have affirmed this time and time again[2]. Perhaps Justice D.G.H. Bowman said it best:

“The appellant argues with great conviction that he should be entitled to rely on advice given by the CCRA and relied upon by him in good faith. I agree that the result may seem a little shocking to taxpayers who seek guidance from government officials whom they expect to be able to give correct advice. Unfortunately such officials are not infallible and the court cannot be bound by erroneous departmental interpretations.[3]“

Is it really fair or reasonable that a taxpayer relying on a long-standing interpretation published by the CRA must suffer adverse tax consequences when a court later determines that this interpretation was incorrect? That is precisely what occurred in Collins. That case is the latest and, ostensibly, final judicial decision on whether there are other avenues a taxpayer can take to seek relief from adverse tax consequences of having completed a transaction in reliance upon a CRA-approved interpretation of the Act that is incorrect.

The SCC denied Collins Family Trust (the “Trust”) the ability to undo a transaction that had been completed in reliance on an interpretation of the Act that had long been accepted as correct by both the tax community and, explicitly, by the CRA. The main issue in Collins revolves around whether the equitable remedy of “rescission” of a series of transactions (which, if granted, would have cancelled the transactions altogether and returned the parties to their respective original pre-transaction positions) should be available to the Trust, in the context of an asset protection plan involving tax planning. The asset protection and avoidance of tax liabilities objectives of the plan were of equal importance (i.e., this plan was not primarily tax motivated).

The Collins decision is another step in furthering the burden put on taxpayers to understand, interpret and comply with the myriad of complex provisions of the Income Tax Act. Even basic tax planning transactions frequently have very complex technical elements, all of which must be followed, and honest mistakes will occur. Equitable remedies used to be available to correct these mistakes, but this is no longer the case. Now more than ever it is essential for taxpayers to have obtained professional tax planning advice from technically competent firms prior to completing transactions.

Background

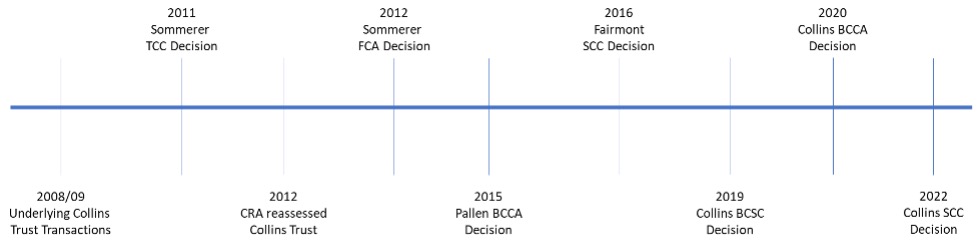

To provide greater context of the legal environment leading up to the Collins decision, a timeline may be appropriate:

- 2008: The Trust was involved in a series of transactions pursuant to which it purchased shares of a corporation (“Opco”) from another corporation (“Holdco”) at fair market value. Opco subsequently declared dividends on its outstanding shares that were owned by the Trust (which dividends were expected to be attributed to Holdco pursuant to subsection 75(2), based on the CRA’s long-standing published interpretations[4]). The expected result was that Holdco would include the dividends in its income (claiming an offsetting deduction pursuant to subsection 112(1)) and the majority of the cash or assets resulting from the Trust’s receipt of those dividends would remain with the Trust (thereby protecting that cash or assets from claims that could be brought by creditors of Opco).

- 2011: The Tax Court of Canada ruled in an unrelated case (Sommerer[5]) that the long-standing CRA interpretation was incorrect, and that the subsection 75(2) attribution provision does not apply to property that is sold to a trust at fair market value by a person other than the settlor of the trust. The CRA was in the process of appealing the Sommerer decision at the same time as it was reassessing the Trust on the basis that the Sommerer decision was correct! The reassessment issued by the CRA to the Trust required that the dividends paid to the Trust be included in its income for income tax purposes, which would be subject to tax at the highest marginal personal tax rates.

- 2012: The Federal Court of Appeal upheld the Sommerer

- 2015: The British Columbia Court of Appeal (“BCCA”) granted rescission in the Pallen[6] case, which had substantially the same facts and transactions as Collins. The BCCA upheld the decision that the taxpayer should be able to rescind the dividends and place the parties back to their original position. The Court in the Pallen case determined that to subject the taxpayer to the CRA’s reassessment only after the Sommerer decision was unfair:

“What took this case “into the zone of unfairness” in the chambers judge’s mind was the existence of the “common general understanding” regarding the operation of s. 75(2). Had the understanding been less certain, he said, the assumption of risk-taking on the part of the trustee would likely have led him to the opposite conclusion.”[7]

- 2016: The SCC, in the Fairmont Hotels[8] and Jean Coutu[9] cases, found that the equitable remedy of rectification (amending a transaction to reflect the parties’ intentions) is not available where the intended tax result was not achieved. In Fairmont Hotels, the taxpayers intended that certain transactions be carried out in a tax neutral manner, however, the transactions entered into resulted in the taxpayers incurring tax. The SCC determined that rectification should be available to “correct” a transaction only where the transaction was not implemented as agreed upon, and that rectification should not be available to correct a transaction in order to achieve the intended result. Following the SCC’s decisions in the Fairmont Hotels and Jean Coutu cases, many tax practitioners were hopeful that the denial of the equitable remedy of rectification in those cases would not preclude a grant of the different equitable remedy of rescission from continuing to be available in the case of transactions that were entered into under a mistaken assumption about the facts or the law.

- 2019: The British Columbia Supreme Court granted rescission in the Collins case based on the BCCA’s decision in Pallen, which the Court felt bound to follow (otherwise it appears rescission may not have been granted).

- 2020: The BCCA decided that rescission should be available in the Collins case and that the Fairmont Hotels case should be interpreted narrowly, as to apply to rectification only and not to all types of equitable remedies.

- 2022: The SCC reversed the BCCA Collins decision, finding that rescission should not be available to annul the transactions and that the Trust should be subject to tax on the dividends paid to it. In the majority decision, the SCC held:

… the Minister was bound to apply Parliament’s direction in the Act, as interpreted by a court of law, unless and until that interpretation is judged to be incorrect by a higher court. Unless a statute gives the Minister the power to deviate from that direction, the Minister may not deviate; nor may a court undermine that direction by resort to equity, since there is nothing unconscionable or unfair about the Minister administering the Act as Parliament directs. Equity is the conscience of the common law, not of Parliament.[10]

The one dissenting Justice disagreed, however, stating:

“In my view, what takes this case into the zone of unfairness is not the application of the law, but rather the CRA’s discretionary decision to reassess the taxpayers based on a retroactive approach to s. 75(2). Unfairness results when the CRA reverses a longstanding interpretation and then seeks to reassess a taxpayer retroactively.”[11]

Debating the merits of the dissenting Justice’s position may be appealing, however any such discussion would be purely academic as the majority of the SCC found in favour of the Crown and the law of the land is now that Fairmont Hotels should be interpreted broadly as to be applicable to all types of equitable remedies.

Takeaway

Taxpayers and tax advisors need to be aware that there are four main principles that should be applied to determine whether any equitable remedy is available to a taxpayer:

- Tax consequences do not result from a taxpayer’s motivations or objectives. Rather, the tax consequences result from the freely chosen legal relationships, as established by their transactions;

- Taxpayers should not be denied the benefit of minimizing their tax liability, which would be achieved based on the ordinary operation of the Act, however, this also cuts the other way: taxpayers should not be afforded relief from an increased tax liability by that same ordinary statutory operation, based solely on what they would have done had they known better;

- It is not a question of whether the Crown or the taxpayer would receive a benefit; rather, the question is what did the taxpayer agree to do, and that alone is what will dictate the tax consequences; and

- A court may not modify an agreement (or other instrument) merely because a party discovers that it results in an adverse and unplanned tax liability.

The key takeaway is that it will be nearly impossible to obtain any equitable relief in the tax context unless the high bar set-out in Fairmont Hotels is met, whereby mistakes may be corrected only where:

- it can be established to a court’s satisfaction that a document does not accurately record an agreement, or

- a party can show that another party knew or ought to have known about a mistake and derived a benefit from the mistake (amounting to fraud).

These restrictions are very limiting and will likely not be applicable in the vast majority of cases. What this means for taxpayers is that they need to be aware and have a thorough understanding of the consequences of any tax planning transactions, “eyes wide open” so to speak. Furthermore, it is imperative to understand that CRA published interpretations should not invariably be relied upon; while they often are helpful and welcomed, they could be incorrect. The advice of skilled tax professionals definitely should be obtained in both planning and implementing a transaction.

For tax practitioners, consider adding a caution to engagement agreements regarding the risk of relying on CRA published opinions regardless of how long-standing they may be, and have conversations with clients emphasizing that the CRA’s published interpretations are neither law nor binding on the CRA. It is also of paramount importance that any tax planning transaction be implemented precisely as intended and be rigorously reviewed.

A Word about Advance Tax Rulings

Advance tax rulings provided by the CRA still have a purpose in the tax arena as they allow taxpayers the ability to have the CRA provide its view on whether a proposed transaction will provide the result the taxpayer is expecting. Technically speaking, advance tax rulings have always been non-binding on the CRA, however their past practice has been to honour the rulings provided with certain reasonable caveats. The use of advance tax rulings may reduce the risk of having a transaction be reassessed by the CRA, however, even the dissenting opinion in Collins provided “But even if the respondents had asked for an advance ruling, the CRA’s advance rulings do not constitute law and are not binding on the courts”[12]. Advance tax rulings may provide insight into how the CRA currently views a transaction; they do not afford protection from the CRA’s misinterpretations of tax law.

End of the Road?

The SCC ruling, in the wake of the Collins decision, has effectively shut the door to any equitable remedies to alter the tax consequences of “mistakes”. However, one ray of hope remains. In his reasons for judgment, Justice Brown stated: “If there is to be a remedy, it lies with Parliament, not a court of equity”[13]. It is open to provincial legislatures to take measures to statutorily empower their respective provincial courts to issue orders of rectification, rescission and other equitable remedies where the context of a transaction can be taken into account and discretion used by a court to decide whether to correct a mistake where it would be unfair to leave it uncorrected, or to hold taxpayers accountable where the facts support a finding that “retroactive tax planning” is sought.

Provincial courts could be handed these tools and many in the tax community (including our Firm) are reaching out to their respective provinces to make the case to provide the courts with these tools. However, until such time, Collins and Fairmont Hotels are law in Canada so taxpayers will be required to bear the tax burdens of their transactions regardless of the circumstances surrounding them.

[1] The Income Tax Act, RSC 1985, c.1 (5th Supp.), as amended.

[2] Moulton v. R., 2002 CarswellNat 262, [2002] 2 C.T.C. 2395, 2002 D.T.C. 3848(TCC).

Goldstein v. R., [1995] 2 C.T.C. 2036, 1995 CarswellNat 438 (TCC);

Watanabe v. R., 1999 CarswellNat 459, [1999] 2 C.T.C. 2962, 99 D.T.C. 822 (TCC);

Michaud v. R., 2011 CarswellNat 5422, 2011 TCC 573, 2012 D.T.C. 1048 (TCC); and

Wellington v. R. (2004), 2004 TCC 313, 2004 CarswellNat 1107, [2004] 3 C.T.C. 2402, 2004 CarswellNat 5802 (TCC) to name a few.

[3] Moulton v. R., 2002 CarswellNat 262, [2002] 2 C.T.C. 2395, 2002 D.T.C. 3848 (TCC) at para 11

[4] E.g., Technical Interpretation Bulletin IT-369R, CRA Views 9332575, CRA Views 2002-0118255, CRA Views 2004-0086941C6, and CRA Views 2001-0116045.

[5] Sommerer v. R. (2011), 2011 CarswellNat 1157, 2011 CarswellNat 4026, 204 A.C.W.S. (3d) 674, [2011] 4 C.T.C. 2068, 2011 D.T.C. 1162 (Eng.), 2011 TCC 212, 2011 CCI 212 ((T.C.C.)).

[6] Pallen Trust, Re, CarswellBC 1326, 2015 BCCA 222.

[7] Ibid at para 56.

[8] Canada (Attorney General) v. Fairmont Hotels Inc., 2016 CarswellOnt 19252, 2016 SCC 56.

[9] Jean Coutu Group (PJC) Inc. v. Canada (Attorney General), 2016 CarswellQue 11182, 2016 SCC 55.

[10] Collins at para 26.

[11] Ibid at para 80.

[12] Collins at para 89.

[13] Ibid at para 11.

Related Blogs

Have you ever wondered how much your US citizenship is costing you? Why renouncing could save you hundreds of thousands and open new doors for financial opportunities.

As US expats prepare for another expensive and stressful tax filing season, we’ve compiled a list of...

Looking to make 2024 your last filing year for US taxes? Here’s what you need to do.

In a recent survey, one in five US expats (20%) is considering or planning to renounce their...

Travelling to the US? If you’re a US expat who doesn’t renounce properly, your trip may never get off the ground.

Air travel can be stressful. Rising airfares and hotel costs, flight cancellations, pilot strikes, long security wait...