Blog + News

Will Charities Suffer from the Proposed AMT Legislation?

The alternative minimum tax (“AMT”) was first introduced in 1986 to ensure that individuals and trusts pay some amount of minimum tax where they otherwise would not (or would pay what was perceived to be an insufficient amount) due to tax preferred forms of income such as gains from qualified small business corporation shares, qualified farm or fishing property, eligible dividends, etc., or by the use of certain preferred deductions or tax credits. While there have been minor tinkering with the AMT since its introduction, the architecture of the AMT has remained the same since its introduction. Well, that is about to change.

The 2023 Federal Budget (the “Budget”) proposed changes to the AMT – to take effect for the calendar year 2024 and beyond – to attempt to “better target high-income individuals”. The 2023 Budget proposals were a follow-up to a 2021 Liberal Party election promise to introduce a 15% minimum tax and a 2022 Federal Budget promise to release proposals to amend the AMT. While a 15% minimum tax was not included in the 2023 Budget proposals, it is clear that these amendments are an attempt to meet the 2021 election promise.

At the time of the Budget, no draft legislation was released. Instead, the Department of Finance (“Finance”) provided guidance on what the new AMT would look like. In the weeks following the budget, many in the accounting, law, and finance communities noted that the new AMT rules may have an adverse impact on charitable giving, particularly for high-net-worth individuals who are, or would like to be, philanthropic. On August 4th, 2023 (following in its long-standing tradition to release detailed draft tax legislation on the Friday of a long weekend), Finance released the proposed legislation with respect to the new AMT, amongst various other Budget proposals.

The concerns around the new AMT’s impact on charitable giving were well-placed. Accordingly, this article will attempt to quantify the new tax cost for high net-worth/high-income individuals on their donations and the potential impact on charities.

One of the main legislative changes that impacts charitable giving is found in the description of “D” in section 127.51 of the Income Tax Act (the “Act”) which limits the “basic minimum tax credit” to one-half of that amount (previously the entire basic minimum credit could be used to reduce AMT). The basic minimum tax credit (defined in section 127.531 of the Act) includes the individual donation credit (section 118.1 of the Act) which means the donation credit, for AMT purposes, is reduced by half for taxation years beginning after December 31, 2023 (i.e., 2024 and beyond)

Before diving into the quantitative analysis, it should be noted that for the vast majority of Canadian taxpayers, the new AMT rules will have no meaningful impact on charitable giving and in many cases, the increased AMT exemption (from $40,000 to the start of the fourth federal tax bracket, approximately $173,000 for the 2024 taxation year) should decrease the applicability of the AMT to most taxpayers. Additionally, any amount of AMT in excess of tax otherwise payable can be carried forward to reduce tax in future years (where the individual is not subject to AMT, of course).

That said, let’s crunch some numbers to get a sense of the impact on charitable giving by comparing the new AMT to the old AMT. The following set of examples compares the impact of the AMT on a hypothetical high net-worth/high-income individual earning $5,000,000 of income. Each scenario depicts a different form of income (i.e., salary, non-eligible dividends, eligible dividends, capital gains, etc.). In each scenario the individual wants to make the maximum donation possible (i.e., 75% of income for the year, pursuant to the definition of “total gifts” in subsection 118.1(1)).

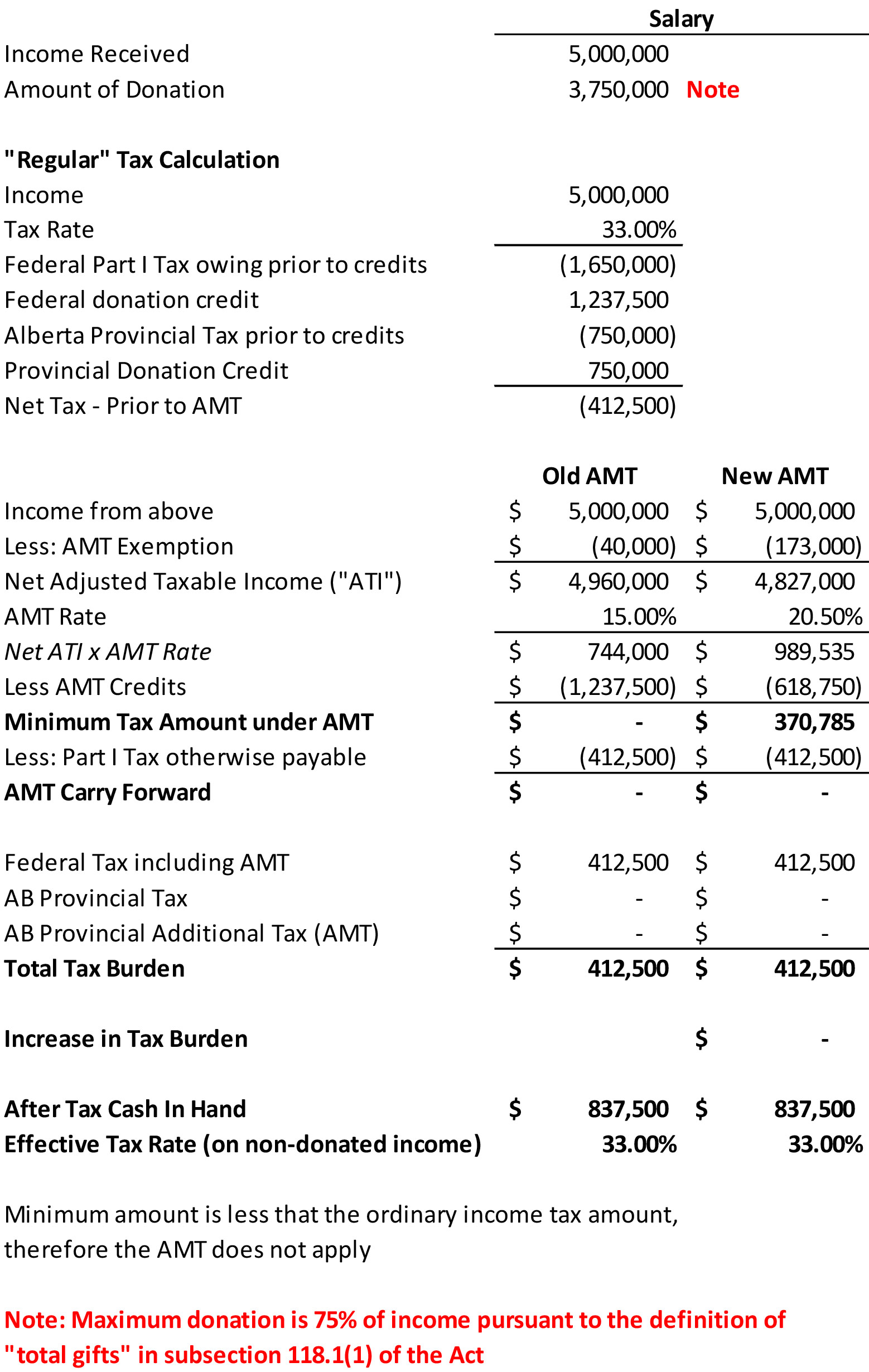

Salary:

First the so-called good news: the federal tax rate on salary and other forms of non-preferred income is sufficiently high that the new AMT should not apply if the sole source of income for a taxation year is taxed at the highest marginal federal non-preferred rate of 33%. However, most high net-worth/high-income earning individuals do not solely, or even primarily, receive income in the form of salary or bonus, so this example is likely too simplistic. We’ll use Alberta as the province of residence of this person, but the provincial impacts for each province should, of course, be checked (note that in most provinces, provincial AMT is calculated as a fixed percentage of the AMT carry forward amount)[1].

_______________

[1] Note for all examples/calculations the following simplifications are used:

- All tax rates are the highest marginal federal and Alberta tax rates.

- All donation credits are calculated at the maximum donation tax credit rate.

- No other deductions or credits are contemplated.

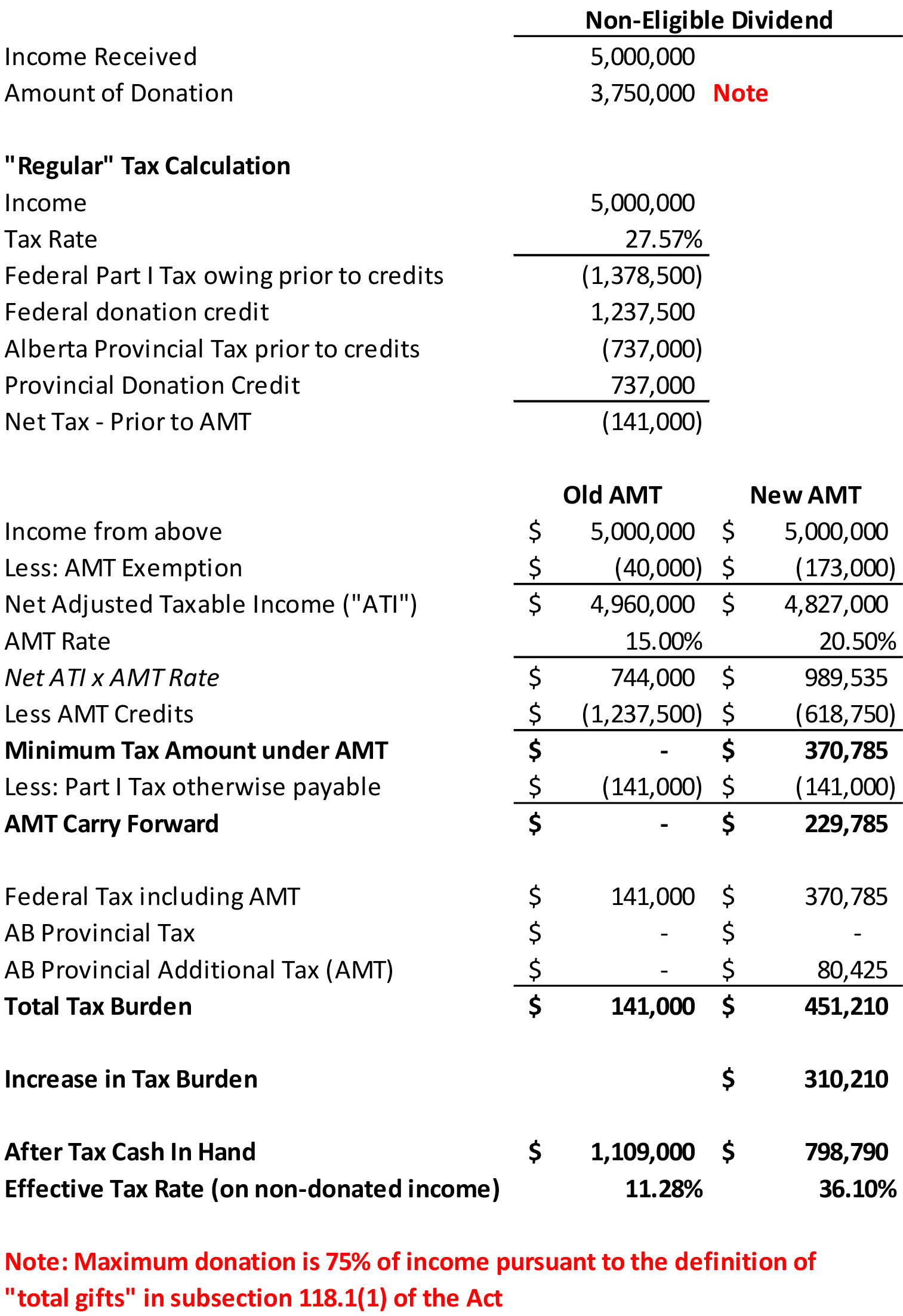

Non-Eligible Dividends:

Where the individual earns non-eligible dividends, the new AMT has a large impact. As you will see from the below, there is an approximate $310,000 increase in tax from the above scenario.

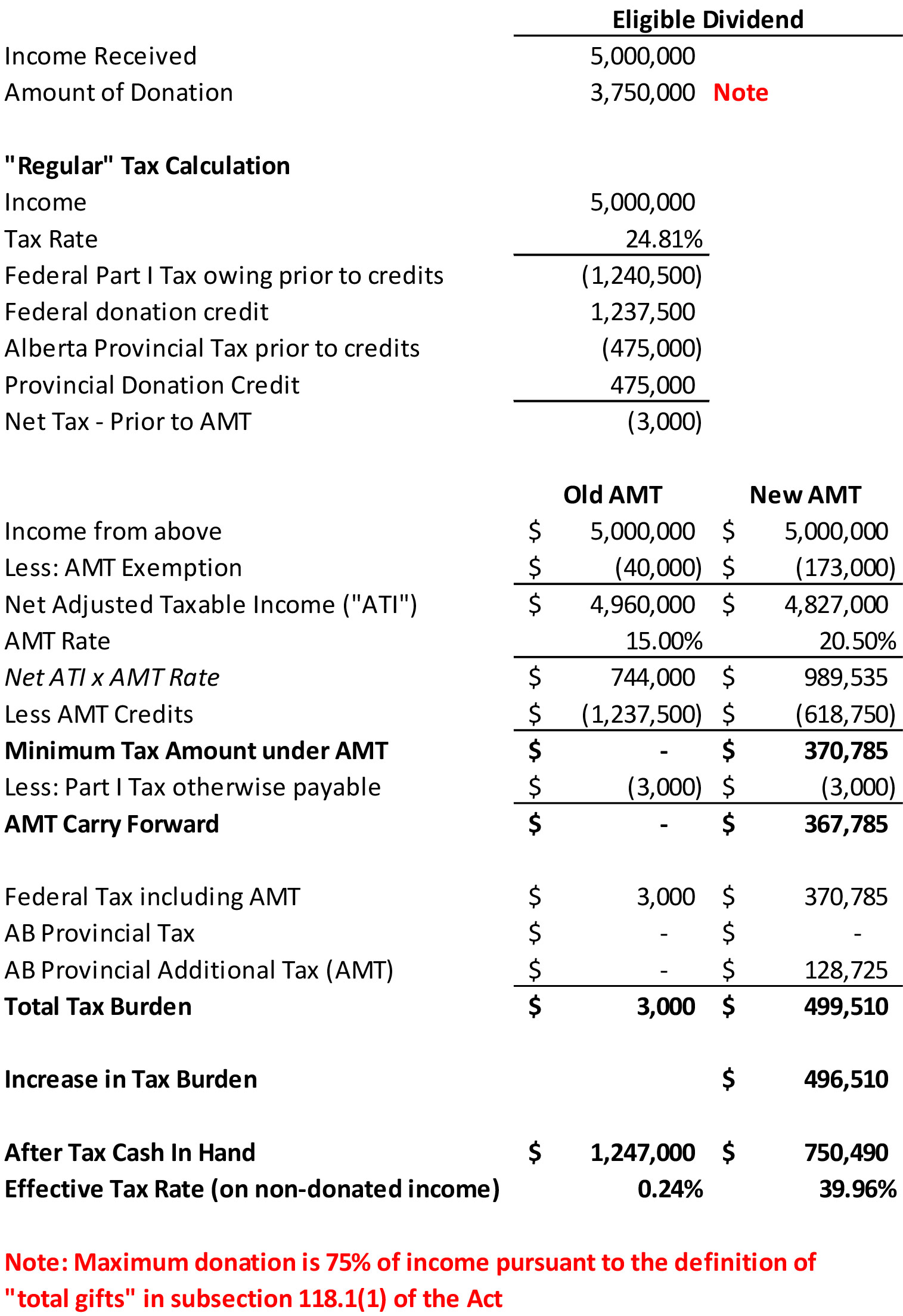

Eligible Dividends:

The impact, unsurprisingly, on eligible dividends is even more pronounced due to the lower effective tax rate on eligible dividends. The upfront cost of the AMT being almost $500,000.

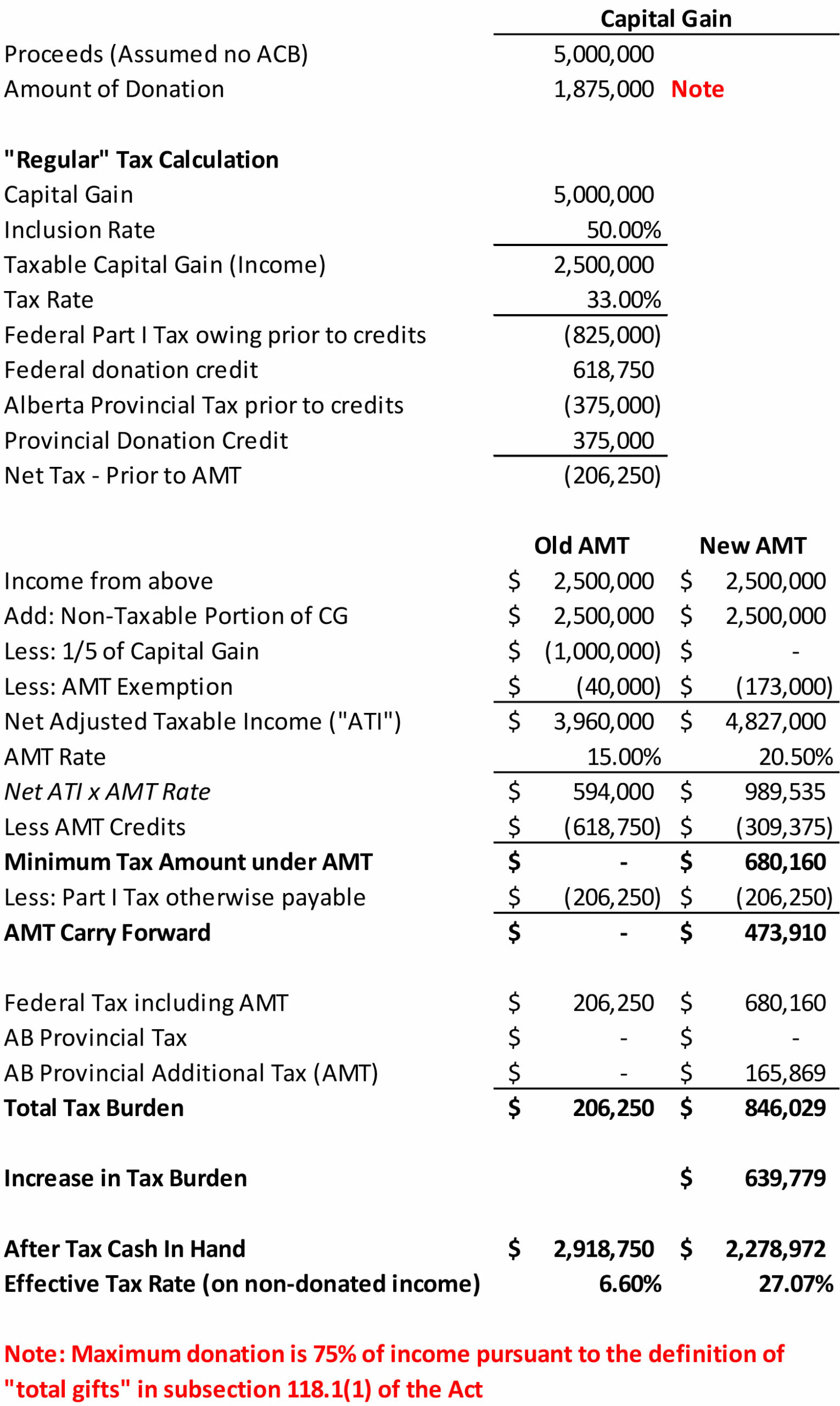

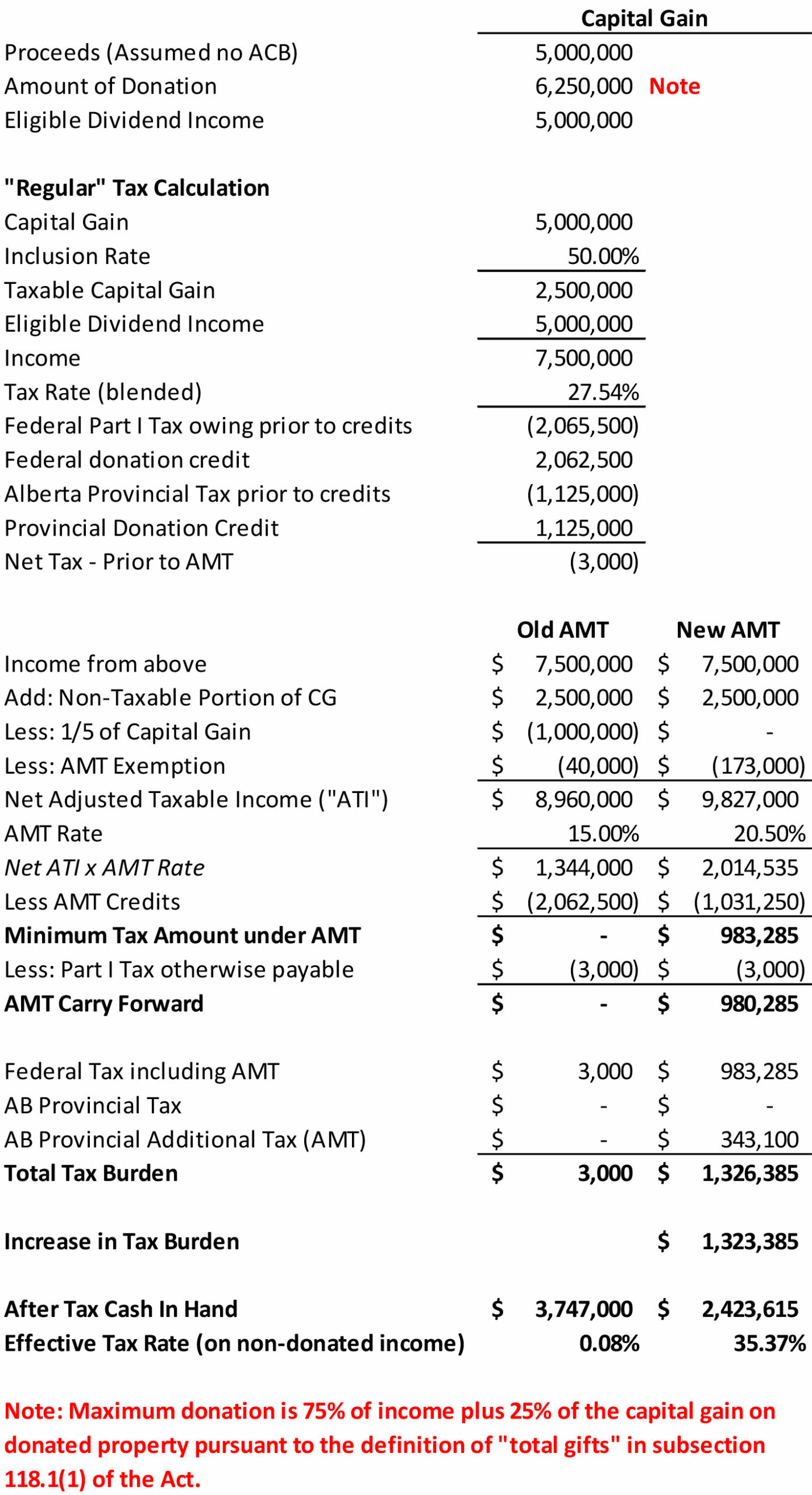

Capital Gains:

Charitable donation planning around an anticipated realization of a capital gain tends to be a bit more complicated as gifts of capital property generally increase the donation capacity by 25% of the value of the donated property (pursuant to subparagraph (a)(iii) of the definition of “total gifts” in subsection 118.1(1) of the Act). Essentially, this means where a donation of sale proceeds is something a taxpayer is planning on, it is advised that the taxpayer donate the property directly to the charity and have the charity dispose of the property, as opposed to the taxpayer selling the property and donating a portion of the proceeds. The new AMT however is particularly punitive when a taxpayer realizes a capital gain and has large donations. For simplicity, the below example for capital gains assumes that property was not directly gifted to a charity, rather the property was sold and a portion of the proceeds was gifted. (Note: in the example below the capital property is not eligible for the lifetime capital gains exemption)

One other point that should be mentioned is that the highest marginal federal tax rate on capital gains is 16.50% which is less than the “AMT rate” of 20.5%. Therefore, simply realizing a capital gain in isolation will often result in a taxpayer being subject to the AMT.

Gifting Property to Charity to Reduce Other Income:

In reality, a high net-worth/high-income individual may use donations of capital property and claim the donation credits to offset tax on other forms of income. Below illustrates the impact of the new AMT on a situation where an individual donates capital property that is not public securities or is eligible for the lifetime capital gains exemption (e.g., real estate) directly to a charity (along with additional cash) and has significant eligible dividend income.

The impact of the AMT is pronounced, at $1.3 million of increased immediate tax, to say the least.

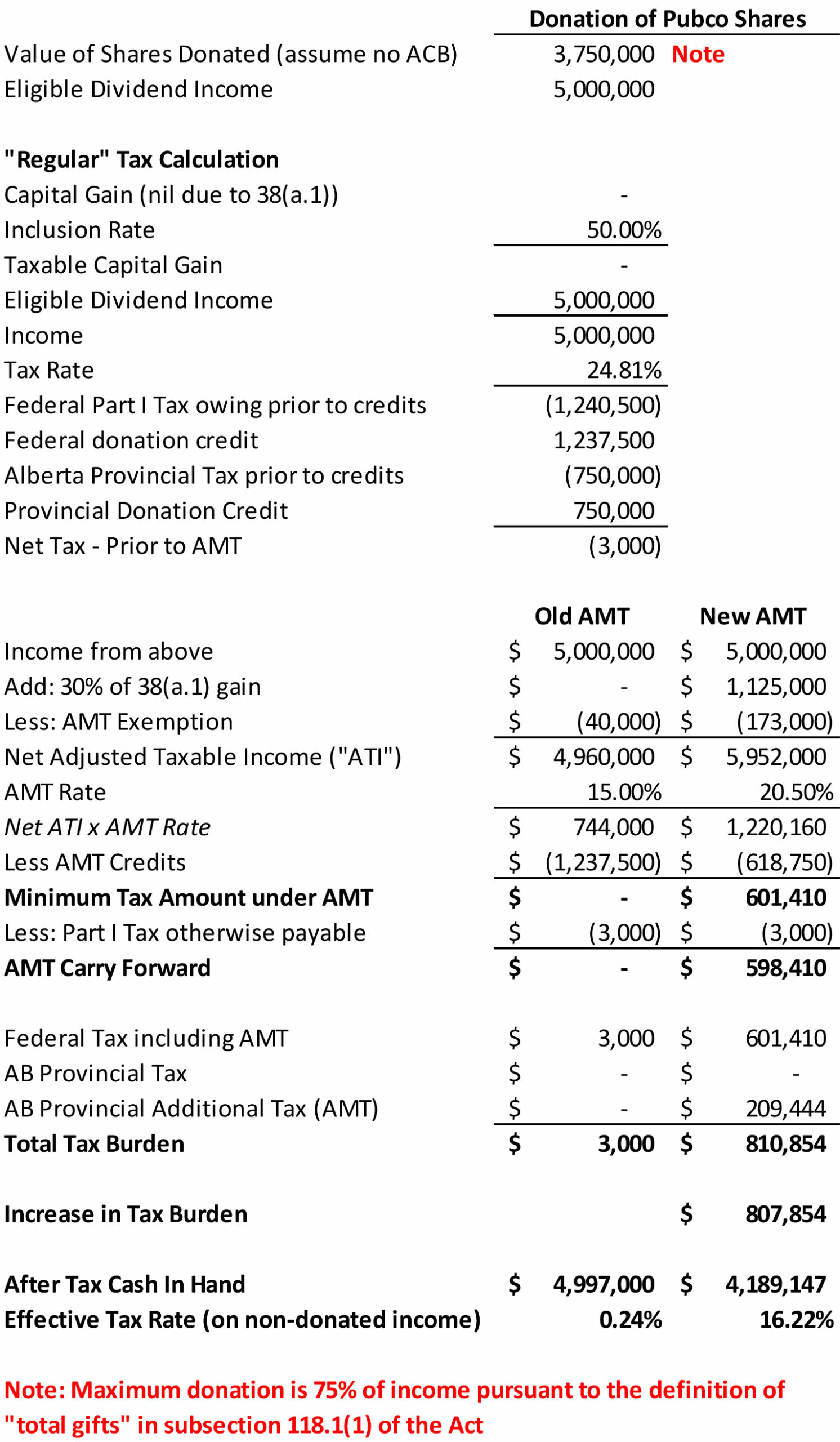

Donations of Public Securities

The new AMT rules also propose to increase the inclusion rate of donations of public securities to charities for the purposes of the AMT calculation. Pursuant to paragraph 38(a.1), capital gains realized on the donation of public securities are not included in the calculation of income, and the current legislation makes no adjustment for AMT purposes. The proposed AMT legislation (in proposed paragraph 127.52(1)(d.1)) now includes 30% of the capital gain from the donation of public securities for the purposes of the AMT calculation.

The increase of roughly $800,000 is certainly significant, but the effective tax rate on the dividend income of 16% is close to the initial policy objective of requiring a minimum tax of 15% to be paid. It should also be noted that that in all of the scenarios, the taxpayer has contributed significant value to charities.

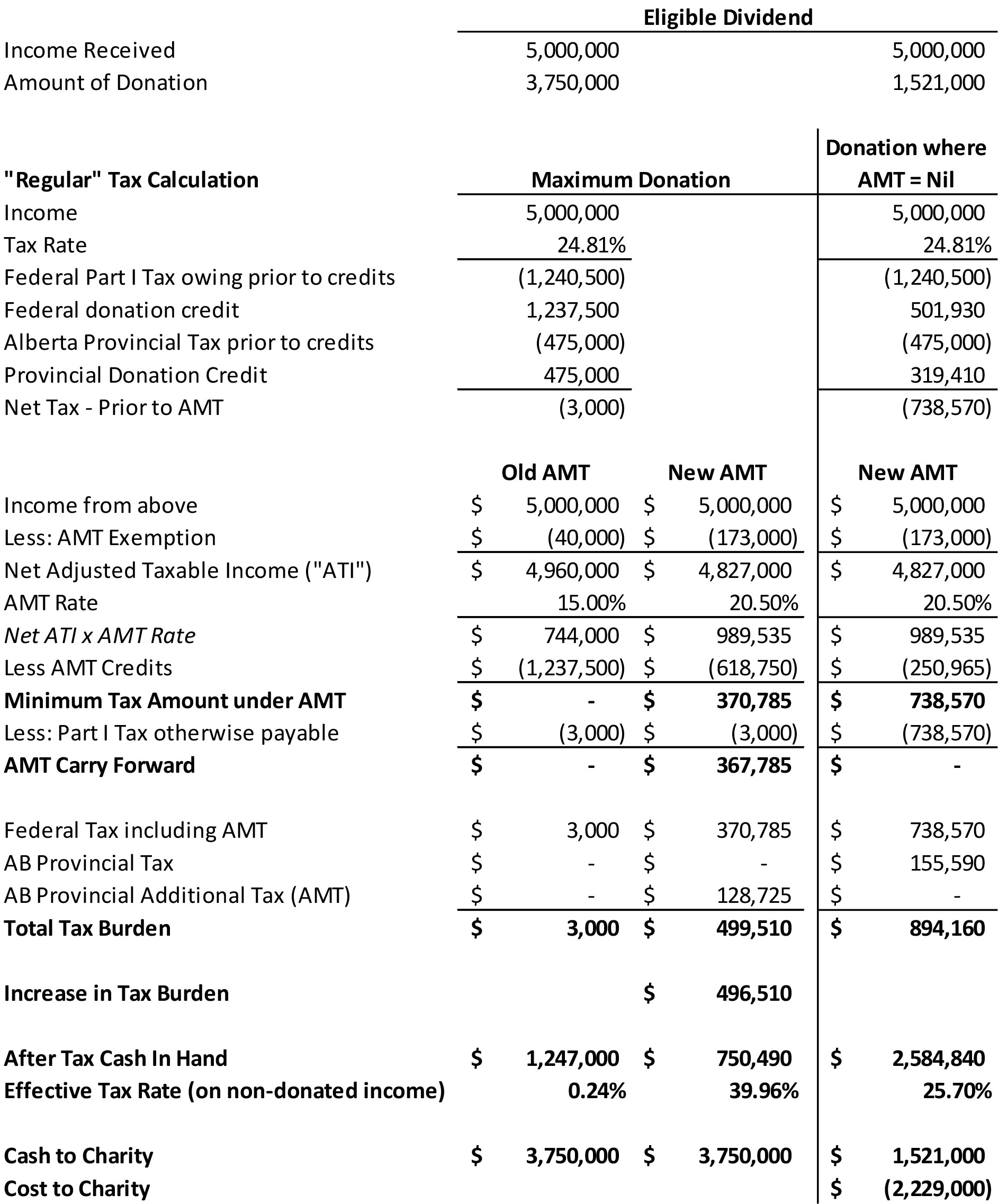

The Cost to Charities

Based purely on the notion that an individual does not want to be subject to AMT, how would their charitable giving be impacted? Let’s return to the eligible dividend example from above. In a vacuum, the hypothetical taxpayer would reduce their donated amount until the AMT amount was equal to the tax otherwise payable. The result would be:

The result is approximately $2.2 million in reduced donations!

Not every philanthropist will take this approach, maybe none will, but it is conceivable that some may take this route and at the end of the day it may be the charities that bear the cost of this proposed legislation. You will undoubtably have noticed that the government tax revenues have increased substantially for this hypothetical individual.

Closing Comments

What will be the impact that the new AMT will have on charitable giving? At this point, it is hard to quantify. As explained above, the vast majority of Canadian taxpayers will be unaffected by this proposed legislation. However, high net-worth / high-income individuals faced with an increased tax burden may alter their philanthropic practices. It would be obtuse to say that the only reason taxpayers donate to charity is because of the low tax cost to do so. However, there is certainly a portion of the population that gives to charity due to tax neutrality. The very policy purpose behind the donation credit is to encourage taxpayers to donate to charities. With the increased tax burden, in the form of the AMT, there may very well be a decline in charitable giving amongst those affected. Even though the AMT is recoverable in future years, many philanthropic individuals donate large amounts each year and these individuals (or individuals who cannot incur sufficient future income, such as people who have a one-time large liquidation event or big retirement income event) may have little use for AMT carry- forward amounts.

As mentioned at the beginning of this blog, the proposed AMT changes are expected to be applicable for taxation years beginning after December 31, 2023. Therefore 2023 provides one final opportunity to plan to donate to charity under the current rules.

The proposed AMT changes, according to the government, were to ensure that the wealthiest Canadians pay their “fair share” of tax. However, the government failed to mention that a portion of the “fair share” may come at the expense of charities that provide valuable services to Canadians. It would be good if charitable donations were exempted from the AMT amendments.

Issues with the new AMT and Certain Trusts

Under the current AMT regime trusts, except graduated rate estates (“GREs”), are not granted the AMT exemption amount of $40,000 (to be increased to the start of the fourth federal tax bracket under the proposed legislation). This remains the case under the proposed legislation, except for qualified disability trusts (defined in subsection 122(3) of the Act). Thanks to proposed amendments to paragraph 127.55(f), GREs should be exempt from the AMT regime for 2024 onward.

Another amendment that is proposed in the AMT legislation is the limitation of various deductions in determining an individual or trust’s adjusted taxable income for AMT purposes, which may result in permanent AMT in certain trusts (it is expected that personal or family trusts will be the most likely to be impacted).

Proposed paragraph 127.52(1)(k) of the Act, generally, limits certain expenses to 50% for the calculation of adjusted taxable income for AMT purposes. The limited expenses include certain office and employment expenses, interest and financing expenses that relate to borrowed money used to generate income from property, CPP/QPP contributions of self-employment earnings, moving expenses, child-care expenses, and disability support deductions.

Now that certain expenses are limited to 50% in the proposed legislation, it is far more likely for a trust to be subject to AMT and have little means to recover the AMT in future years resulting in a permanent tax.

For example, a trust earns $1,000 of property income and has $800 of interest expense that was deductible in determining the trust’s income[2]. The net income of $200 was paid to the beneficiaries of the trust. For income tax purposes, the trust has no taxable income, as the $200 payment to the beneficiaries is deductible pursuant to subsection 104(6) of the Act. However, for AMT purposes, the adjusted taxable income is $400 (as 50% of the interest is not deductible due to proposed paragraph 127.52(1)(k) of the Act). Because family trusts do not have any AMT exemption amount, the AMT will be $82 ($400 * 20.5%). Even with minimal gross income, family trusts and other trusts can be subject to AMT.

The interaction of the proposed AMT legislation can make it difficult for trusts to recover the AMT carry forward in future years, which could result in the AMT being permanent and essentially a form of double taxation. Family trusts with interest and financing expenses should be cognizant of the proposed legislation and make adjustments, if necessary, to reduce the impact of the new AMT.

[2] Which could have been the result of a prescribed rate loan strategy.

Related Blogs

Have you ever wondered how much your US citizenship is costing you? Why renouncing could save you hundreds of thousands and open new doors for financial opportunities.

As US expats prepare for another expensive and stressful tax filing season, we’ve compiled a list of...

Looking to make 2024 your last filing year for US taxes? Here’s what you need to do.

In a recent survey, one in five US expats (20%) is considering or planning to renounce their...

Travelling to the US? If you’re a US expat who doesn’t renounce properly, your trip may never get off the ground.

Air travel can be stressful. Rising airfares and hotel costs, flight cancellations, pilot strikes, long security wait...